|

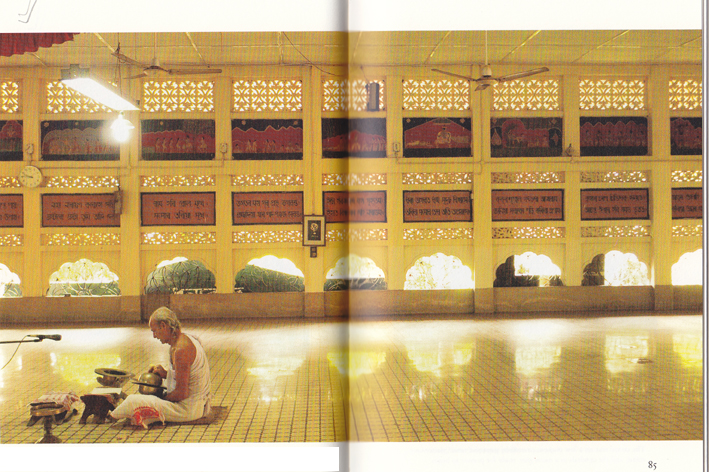

Naam Ghar or Kirtana

Ghar:

Naam ghar

or Kirtana ghar is Sankaradeva�s single most outstanding legacy for

the Assamese people. The focal point of his religion, its influence on

Assamese life is all-pervading. An epitome of simplicity, Naam ghar

has been the cornerstone of

Assam�s

socio-religious structure for over half a millennium.

Basic in design,

naam ghar is a large prayer hall, built in the traditional style and

generally placed in an east-west direction. Its open sides are symbolic of

its acceptance of people of every caste and creed. It has an adjunct, the

�sanctum sanctorum� known as the �monikut� where valuables and

scriptures are kept. In place of idol, the Bhagawata or its concise

version Gunamala is placed in the Monikut. Sometimes, other

scared texts-the Kirtana Ghosa or Dasham-Adi (the first part of the

tenth chapter of the Bhagawata), both by Sankaradeva; the Naam Ghosa

or Bhakti Ratnavali by Madhavadeva, are also placed in the

monikut. Today, many kirtana ghars, including Barpeta, allow

idols of Lord Vishnu or one of his avatars in addition to the sacred

books.

The eminent artist and

filmmaker Jyoti Prasad Agarwala (1903-51), while on a visit to Berlin in

1930, saw there a few newly constructed community centres. He was struck

by the uncanny similarities in their design and concept to Sankaradeva�s

prayer hall, the naam ghar, conceived four centuries earlier. Upon

his return to Assam in 1931, he closely examined the sculptures and

paintings at Bardowa xatra. He found further echoes, this time of

the �revolutionary� modern sculptures of Jacob Epstein (1880-1959) he had

just seen in London. Even the altar, the multi-stepped throne for the

�sacred book� reminded him of Cubism, an art form of the early 20th

century.

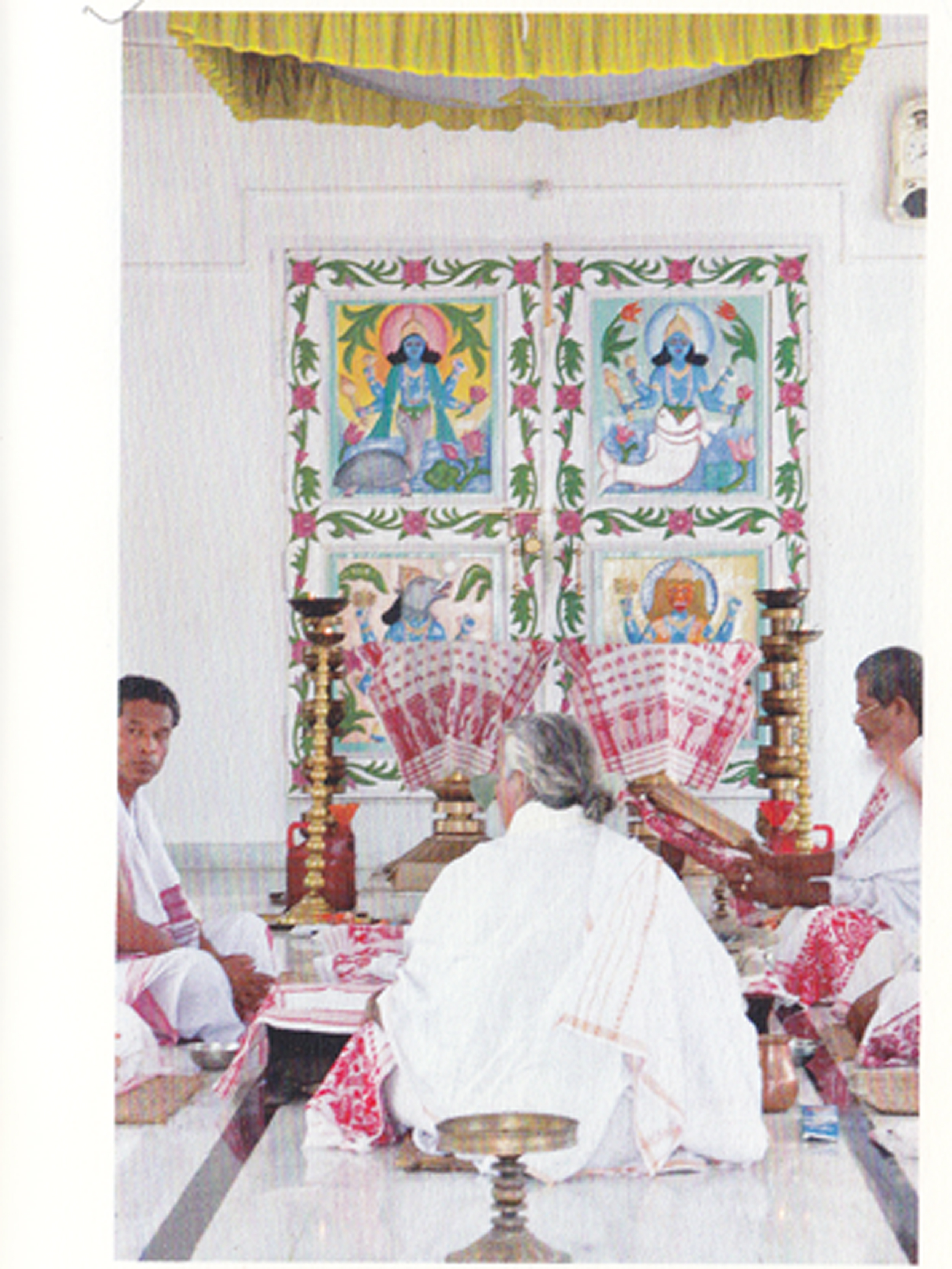

Inside a naam ghar,

equality is preached as well as practiced. During ceremonies, everybody

sits cross-legged on the floor with bare feet, and partakes of the same

Prasad. The devotees, irrespective of caste, creed or speech, chant the

name of Lord Krishna during three broad sessions of naam prasanga

a day, marketing the morning, afternoon, and evening prayers. Madhavadeva

later increased this to fourteen; a practice followed to this day at

Bardowa and Barpeta kirtana ghars. Worship involves the burning of

incense, lighting of earthen lamps, and other rites. An akshaya banti,

the eternal lamp symbolic of the light of faith, is kept alive by a

continuous supply of oil.

Naam ghar

is, however, more than a mere congregational hall of prayer. It brings

about a degree of bonding within the community through people praying

together and participating in its various activities. It is a confluence

where various social issues, including disputes and developmental

activities affecting the community, are discussed. Here, all sections of

society assemble and arrive at decisions through a democratic process.

Nobody is barred from expressing his views on matters under discussion. In

many respects, naam ghar assumes the role of a village parliament

albeit without legal or judicial sanction. It provides a platform for

grass-root democracy, and can be termed the precursor of Panchayati Raj

now being actively espoused.

For more than 500

years, Sankaradeva�s naam ghar has been the focus of his teachings

and dots every nook and corner of Assam.

Xatra

Inspired by

Sankaradeva�s naam ghar, his devotees later expanded its

infrastructure to establish xatras. The word xatra finds

mention in scriptures since Vedic times. It has been used to denote

various things or places never straying far from its root, xat,

meaning good or true. In Assamese Vaishnavism, xatra has over the

years evolved to mean a monastery or a habitat where vaishnavites

reside or gather to recite and listen to prayers to the Lord, and

participate in religious and cultural activities. Somewhat similar in

concept to Benedictine monasteries, Buddha Vihars, and Maths

of other monastic communities in India, xatras place great emphasis

on development of art and culture through religious practices.

The xatra

institution is envisaged as centre of society focus, fundamental to the

preservation of diverse traditions of religious learning. Monks train in

all aspects of xatriya life in addition to receiving a general education.

Studying the scriptures in both Sanskrit and Assamese helps them to serve

as responsible functionaries of the xatras. Need for contemporary

education has not been lost on the xatra managements either. Recent

initiative by Phoolbari xatra in noni in Nowgong for

imparting modern technical education is a case in point.

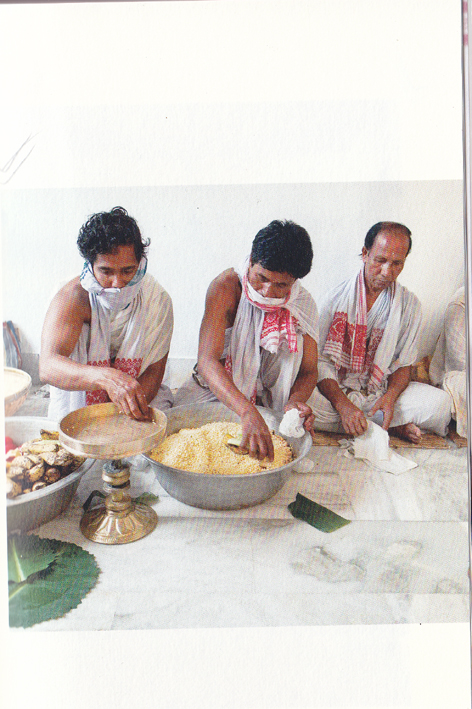

The primary functions

of a xatra are to: propagate Vaishnavism based on the tenet

of monotheism; initiate disciples; provide rules of conduct for neophytes;

and hold religious festivals pooja (worshipping), naam prasanga

(reading of religious books), nritya (dance), geet (song),

art and sculpture.

The hub of all

activities in xatra is the kirtana ghar. The pre-eminence of

the kirtana ghar in the xatra set-up is underscored by the

fact that both Bardowa and Barpeta began with a kirtana ghar.

Sankaradeva�s followers later expanded them into xatras for

disciplined propagation of the various facets of the Vaishnava faith including dance, drama and music.

The xatra, with

its own organizational structure, is run in a democratic manner. The

Xatradhikar is the principle spiritual guide and preceptor; he

initiates disciples and conducts key religious functions. The monks or

bhakats carry out their assigned tasks, and lead a life of devotion.

Both celibate and married monks are allowed within the campus; celibate

devotees are called kevaliya, keval meaning single. Sisyas or

the lay devotees live in the surrounding villages, leading the life of a

householder.

Xatras

derive their income from three main sources: i) land originally granted by

the Kings in pre-colonial days and later ratified by the British, ii)

tithes from disciples, and iii) donations by well-wishers.

Xatras also act as repositories of ancient texts-scrolls on bark

and silk-and documents in original which survive to this day. The

Auniati xatra in Majuli maintains a fine museum for its

collection.

Majuli,

the largest inhabited river-island in the world, is at the centre of the

Vaishnavite culture in

Assam.

The xatriya movement that began in the early 16th

century had its golden period around mid-17th century. The

large xatras of Majuli are of this period: Bengenaati

(1626), Garmur (1650), Auniati (1653), Dakshinpat

(1662) and Uttar Kamalabari (1673). Erosion by the river

Brahmaputra

has reduced Majuli�s area from 1250 sqkm to 650 sqkm. Of its 65

xatras, only 31 remain.

Gradually, the apostles

of the new faith began building xatras for themselves and their

families, and the idea of community service dwindled. Only a handful to

begin with, the Asom Xatra Mahasabha puts the present number of

xatras at more than nine hundred. However, this numerical upsurge has

not translated into greater proliferation of Vaishnava values on

the ground. Through mismanagement and an emphasis on form rather than

substance, the influence of xatras has gradually declined. The

institution of xatra, in true sense of the term, survives only in a

few of them, mainly in Majuli xatras.

Barpeta xatra,

one of the pioneering centres of Sankaradeva�s religion, nurtured by

Madhavadeva, and reputed to have the largest kirtana ghar in Assam,

today does not allow women and Muslims inside its kirtana-ghar, and

barred entry to harijans until a court ruled against the xatra.

However, recent times have seen considerable resurgence in efforts to

revive and conserve the essence of the xatriya traditions. In a

historic moment, on the morning of Sunday, April 4th 2010, under an

initiative by Sri Janaki Ballav Patnaik, Governor of Assam, Pat-bausi

xatra, near Barpeta, where Sankaradeva had spent his most fruitful

years, opened the doors of its kirtana ghar to women, ending

centuries of gender discrimination.

Sankaradeva�s Bardowa

xatra, too, has had a chequered history.

Bardowa Xatra:

After the Bhuyas

left in 1516, the site where Bardowa xatra stood was abandoned, and

for all purposes, lost to the world. Sankaradeva and Madhavdeva after him

never made any attempt to resurrect it during their lifetime; memories of

the trauma Sankaradeva went through in his last days there perhaps a

determinant. Sankaradeva�s kirtana ghar in Bardowa, where he had

spent the first 67 years of his life, perished with time and lay covered

in thick jungle for nearly 150 years.

Finally around 1658,

Kanaklata the principal among the three wives of Sankardeva�s grandson

Chaturbhuja, sought the blessing of the Ahom king Jayadhvaja Singha

(1648-1663), to restore the xatra. Permission was granted.

Kanaklata came and set up camp at Ai Bheti, about 5 miles from Bardowa. She was accompanied by Damodara, Chaturbhuja�s

nominated heir and the son of his sister. Kanaklata was a woman of much ability and great

personality. She was responsible for the considerable furtherance of the

faith of her grandfather-in-law. For the first time in the history of

(Assamese) Vaishnavism, a woman acted as a religious head and

appointed other persons as Superiors.

Kanaklata had the area

cleared and re-established the kirtana ghar at the original site.

Said to have been directed by the wife of an Ahom official to whom

Sankardeva had appeared in a dream, Kanaklata retrieved a stone, buried

near a hilikha or haritaki tree, where Sankardeva is

believed to have done his writings. The stone bearing Sankardeva�s

footprints was placed in a separate house open for public viewing.

There was further

disruption in 1662-63, when Mir Jumla invaded Assam; Kanaklata and

Damodara had to leave Bardowa. During this period of disturbance, they

both managed to secure the patronage of the Ahom king, Chakradhvaja

Singha (1663-69), to establish new xatra in other places. Around 1668,

Kanaklata made an attempt to come back to Bardowa but died on the way at

Kaliabar, near Nowgong. Their descendants continued to look after Bardowa

xatra through several generations.

By the time the Ahom

king Gadadhara Singha (1681-95), came to power, the neo-Vaishnavite

sects, founded on the teaching of Sankardeva, had attained remarkable

dimensions. The country was full of religious preceptors and their

follower claimed exemption from the universal liability to fight and

assist in the construction of roads and tanks and other public works.This

gave the Brahmans an opportunity to turn the king�s mind against

Sankardeva�s religion and its followers. The king ordered the demolition

of all Xatras and an indiscriminate persecution of the followers of

the religion, �to break their power for good and all.�

Bardowa xatra

was also not spared. The descendants of Kanaklata and Damodara eventually

managed to rescue it by playing a hefty penalty. They continued to

administer it jointly for more than a hundred years until 1799 when an

internal feud regarding ownership arose between the descendants of the two

families. The Ahom ruler, King Kamaleswara Singha (1795-1810),

intervened and resolved the issue by dividing the xatra into two

halves, one called Barphal (senior side) going to Damodara�s

descendents, and the other called Saruphal (junior side) going to

Kanaklata�s, each with its own Kirtana ghar.

Divided thus, Bardowa

xatra continued with its two adjacent Kirtana ghars more

than 150 years till another ruler intervened. After India gained

independence, a group of prominent citizens, led by Sri Motiram Borah of

Nowgong, a minister in the Assam Cabinet, brought the two warring factions

together and, on 2nd October, 1958, established once more the

single Kirtana ghar as it stands today.

Bargeet

While on his first

pilgrimage, Sankardeva was enthralled when he heard devotees sing the

songs of poets. He saw how a soulful lyric sung melodiously takes a

message straight to the devotee�s heart. Deeply inspired, he composed his

first hymn. He later urged his chief disciple Madhavdeva to follow suit.

The devotional songs composed by Sankardeva and Madhavdeva are called

bargeet, songs of Higher Praise.

Sankardeva has

believed to have composed about 240 hymns. Of these only 35 survived, the

rest destroyed in a fire. Sankardeva was distraught at the loss and did

not write any more songs. Madhavdeva retrieved his guru�s songs from

whatever was retained in the memory of the disciples, and composed new

ones himself. In all, they come to 191 and only these, specifically, are

known as bargeet. Both fine singers of bargeet, Madhavdeva

was considered superior to Sankardeva.

Like most

saint-composers of the day, Sankardeva and Madhavdeva used classical

pan-Indian ragas in their compositions. Together, they worked with more

than thirty ragas, the more popular ones being Dhaneshri, Asowari,

Kalyan, Gauri and Basanta. A specific raga is mentioned at the

top of each song. In 25 of his compositions, Madhavdeva had used raga

Bhatiyali, not usually found amongst the prevalent ragas. Bargeets

are primarily prayer songs sung during various services of the xatras,

and are grouped together for singing at different hours of the day. Their

huge popularity among the masses stems from their simple poetry and

soulful melody.

Bargeet

is convergence of philosophical reflections, secular and ethical

broodings, agonies of the spirit, and saintly humility. Each bargeet

invariably concludes with a passionate cry for refuge at the feet of Lord

Govinda, and deliverance from the sufferings of the world. These

characteristics, much in evidence in his composition at school, find

expression in his very first hymn, composed during his first pilgrimage:

�Rest, my

mind, rest on the feet of Rama;

Seest thou not the great end approaching?

Oh mind, every moment life is shortening,

Just heed, any moment it might fleet off.

Oh mind, the serpent of time is swallowing:

Knowest thou death is creeping on by inches,

Oh mind, surely this body would drop down,

So break through illusion and resort to Rama.

Oh mind, thou art blind;

Thou seest this vanity of things, yet thou seest

not.�

It ends with the lament

�Why art thou, O mind, slumbering at ease?

Awake and think of Govinda,

O mind, Sankara knows it and says,

Except through Rama, there is no hope.�

For Sankaradeva, God is his rock; all else,

unstable.

�I fall at thy feet, O Hari, and offer Thee humble

prayers to save my soul.

Languishing with the poison of the serpent of the

world,

My life is threatened every moment.

Unstable are men and wealth, unstable is youth and

the world:

Wife and son, they are unstable.

Whom should I turn to as eternal and lasting?

My heart is fickle like water on the lotus leaf;

It does not settle for a moment,

Owns no fear in the enjoyment of the world of

senses.

Thou art my destiny,

Thou art my spiritual guide.

Saith Sankara, steer me across the vale of sorrows.�

Reams of learning and mindless rites and rituals

lead not to salvation.

�The scholar does not see the straight path,

Nor does the performer of a million sacrifices

attain Hari.

Both fall down to earth and anon,

All rites and rituals,

All pilgrimages to

Gaya and Kashi

Made round the years,

All yogas done and rhetoric learnt,

Only cloud the vision

Forget therefore the vanity of learning and rites,

And worship the feet of Hari,

In your innermost soul.�

In this world of

illusion, only faith, adoration and devotion to Krishna or Rama can

release human beings from death, destruction and utter ruin.

�O animal in man�s dress,

In the snare of cravings,

You are a prisoner now,

From this prison-world none can rescue you,

Save your own devotion to the Lord.

Devoutly I serve you Lord Rama;

Let his reside in my heart.

Rama is my most precious treasure.

O Lord, leave me not in the grip of death,

Prays the servants of

Krishna.�

The religious poems of

the English poet Robert Herrick (1591-1674) are called �Noble Numbers�;

Bargeets have been variously described as Noble Numbers, great Songs

Celestial, and also as Holy Songs.

Ankiya Nat or Bhaona

The history of Assamese

drama begins with the plays Sankardeva wrote in early sixteenth century,

Chihna Yatra being the first spark of his imagination. These plays are

popularly known as ankiya nat while their staging is known as

Bhaona. �Ankiya� means �one act� and �nat� means drama; it is

also described as Ek Anka, or a �continuous act in one sitting�. Sankaradeva has to his credit six plays written between 1518 and 1568.

The inspiration for the dramatic narrative is the Bagawata, with

the exception of one which draws upon the Ramayana. Working with the

ageless elements of the ancient scriptures and the epics, Sankaradeva gave

them an idiomatic agency that places them dramatically and firmly amongst

the people.

Indigenous theatrical

elements like the Dhuliya (drummer) and Oja Pali (band of

singers) predate Sankaradeva. Sankardeva blended the existing elements

with classical Sanskrit ideals in creating his ankiya nats, his

bhaonas. As in the case of bargeet, only the plays written by

Sankaradeva and Madhavadeva are termed ankiya nat proper; while the

presentation of such drama in situ is called ankiya bhaona. Plays

by other, written in the same format and presented in an identical manner,

inhabit the general category of bhaona.

The main objective of

the play is to evoke a sense of devotional fervour in the audience. The

plot is so woven as to glorify the Lord, Krishna or Rama. The dramatist

aims neither for originality of narration nor realistic portrayals. While

the language used in the ankiya nat is Brajabuli, newer

plays continue to be written in standard Assamese, and so the tradition is

living one.

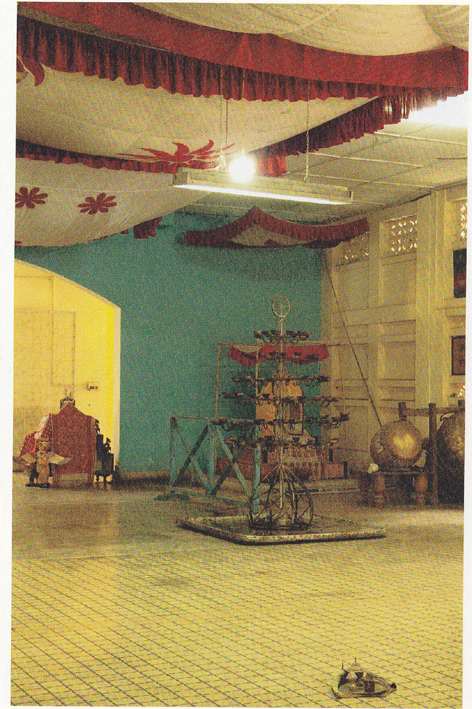

The one-act plays are

characterized by shimmering white costumes for the orchestra and rather

fanciful effigies for the actors. The performers enact their roles wearing

masks of gods, goddesses, demons, and animals. These masks are enormous,

often extending as far down as the waist of the performer, some as big as

15 feet in height. Through a combination of movements and gestures

appropriate to the mask he inhabits, the performer brings to life its

mythical concomitant. The governing idea is the creation of a grand

spectacle that readily appeals to the masses. The orchestra providing

musical accompaniment to these dramatic presentations is called, simply,

Gayan (singer) and Bayan (instrumentalist).

The pivotal role in

a bhaona is that of the Sutradhar or the narrator. The

principal objective being to propagate Vaishnavism, songs and

dialogues in the vernacular are interspersed with slokas and other

pieces in Sanskrit. The characters and events are allowed a certain

fluidity and openness to extemporize during the play, as with performance

of Indian classical music. But there is no break in the narrative flow

itself. The Sutradhar strings together all the components: he proclaims

the theme, announces the entrance and exit of each character, elaborates

the different situations, and leads the benedictory singing. Patently,

this

position requires the most varied qualifications: an ability to sing,

dance, recite slokas, and above all, a clear understanding of and close

engagement with the entire play. Sankaradeva�s Sutradhar has his prototype

in the Oja of Oja Pali (band of singers); the Oja Pali chorus is the

precursor of Sankaradeva�s gayan-bayan.

The usual venue for a

bhaona is the naam ghar. However,it is now customary to stage bhaonas on

platforms away from the xatra and the naam ghar. The last decades have

seen great resurgence in the staging of ankiya nat, evoking greater

appreciation of Sankaradeva�s plays both at home and abroad. Bhaona

samaroh, performance of a large number of bhaonas at one venue over a

period of days, has become popular. The one in Majuli, held annually,

draws a large number of visitors from all parts of India and abroad.

Prof. K. D. Tripathi,

Sanskrit scholar and an authority on Natya Sashtra, traces the

origin of Ankiya Nat to Sangitaka form of theatre dating

back to 1st-2nd century B.C. He describes

Sankaradeva�s ankiya nath as remarkable in terms of its philosophy,

aesthetic and innovative techniques, besides being the oldest and the most

important of the North Indian temple theatre forms.

Xatriya Dance

Xatriya

dance or xatriya is one of the eight principal classical Indian

dance traditions. As the form grew within the xatra, it came to be

known as xatriya dance. While some of the other dance traditions

have been revivals of recent times, xatriya dance has remained a

living tradition since its creation by Sankaradeva in 15th

century Assam.

Xatriya

dance began primarily as an accompaniment to Sankaradeva�s ankiya nat.

Sankaradeva drew elements from various folk and ethnic traditions around

him, and refined them to create his dance form. Like Kuchipudi and

Kathakali, xatriya dance is born of the dramatic tradition,

the characters use dance movements to illustrate various bhavas

(sentiment) and rasas (flavour).The abhinaya (acting) is

indispensable but bhakti is the object or goal of the entire

performance. The xatriya dance tradition also has a separate stream

of dance movements independent of the central dramatic narrative.

The core of xatriya

dance is to present mythological teachings to the people in an immediate

and enjoyable manner. Traditionally, it used to be performed by male

bhakats (monks) in xatras as part of their daily

rituals and during special festivals. Now-a days, it is performed by both

men and women and also outside xatra precincts. The dance is

accompanied by bargeet, and the instruments played are khol

(drum), taal (cymbal) and the flute. Other instruments like violin

and harmonium are recent additions.

Costumes are made of

paat, a traditional Assamese silk, woven with intricate local

motifs. Ornaments are of traditional Assamese design, such as Gaamkharu,

a large bangle with a clasp, Doogdoogi, heart-shaped locket made of

gold and studded with pearls, Lokaparo, two sets of twin pigeons

placed back to back in gold, Satsori and Golpota, necklaces

made in gold and many more.

The xatras had

maintained certain rigid disciplines within their walls, and the dance was

performed in a highly ritualistic manner by male dancer�s alone. This

classical rigidity, adherence to certain principles, and lack of organized

research on the dance form all contributed to its delayed recognition as

one of the classical dance traditions of India. Finally, on 15 November

2000, the Sangeet Natak Akademi accorded it its current status. The

other seven traditions are: Bharatanatyan, Kathakali, Kuchipudi,

Manipuri, Odissi, Mohiniyattam and Kathak. Among the

eight, xatriya dance is the only one that can be traced back

directly to an individual.

The musical component

of xatriya dance is rich in its tonal quality. Circumstantial

evidence points to the culture of dance and music before Sankaradeva's

time. That both Sankaradeva and Madhavadeva sat their compositions to

classical ragas is in itself indicative of a living

tradition. But there is no specimen of raga music composed in Assam, at a

date earlier to Sankaradeva. It is also likely that music was studied

among the Bhuyas; Sankaradeva in one of his self-introductory

verses praises his father Kusumavara as a gandharva (a musician in

ancient texts) incarnate.

By late 19th century,

xatriya dance had emerged from the confines of Assam's xatras ,

from monasteries it moved to the metropolitan stage. Xatriya is now

performed by both men and women, not affiliated to xatras on themes

other than mythological. Its fame and popularity have spread beyond the

boundaries of the country. A workshop on xatriya dance, organized

in Paris from 31st May to 8th June 2010 attracted artistes from as far as

Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Iran besides France. In July 2010, a Japanese

lady with a three-year-old daughter arrived in Assam to learn xatriya

and has since performed on stage in Guwahati.

This brings to focus

the need for setting out the training methods of xatriya outside

the xatra tradition. As in other classical Indian dance traditions,

xatriya dance too possesses a strictly circumscribed curriculum of

training although interestingly, the form is without any written text. It

has been handed down orally through the gurukul system prevalent in

the xatra. Teaching, too, is through oral transmission. It�s now

important to document the present units of dance grammar so that a

benchmark is available for reference. And while doing so, care must be taken

to maintain the essence and philosophy which form the soul of the dance

form. This is the challenge before xatriya today.

Vrindavani Vastra

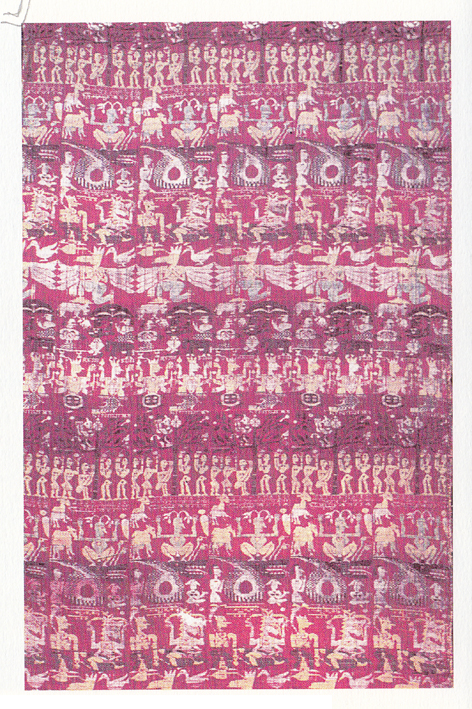

Vrindavani Vastra

brings into focus the range of Sankaradeva's creative genius. Katha

Guru Charita,a chronicle of events during the saint's lifetime, gives

the genesis of Vrindavani Vastra: During his visits to the Koch

Behar royal court, Sankaradeva often regaled Chilarai with descriptions of

the fun-filled childhood days of the young Krishna in Vrindavan.

The prince was enthralled, and wished he could partake of the experience

by sniffing Sankaradeva's lisps he spoke. Sankaradeva replied that,

for the prince's enjoyment, he would have the narrative inscribed on cloth

in a graphic form.

He engaged the weavers

of Tantikuchi, near Barpeta, to weave a forty-yard-long panel of

tapestry depicting Krishna's early life in Vrindavan. Sankaradeva

provided the designs to be woven, chose the various colours of the threads

to be used, and personally supervised the weaving. It took about a year to

complete and, deriving its name from its theme, came to be known as the

Vrindavani Vastra. When first unveiled for viewing, people were

astounded to see the true-to-life depictions of Krishna�s activities in

Vrindavana, the exuberant colours, in woven captions, and exclaimed

that the cloth has come from the heavens and its makers is not a human. A

little before Sankardeva�s death in 1568, he is said to have presented it

to Chilarai and Naranarayana who were both overwhelmed with the result.

How and when it disappeared from Koch Behar is not known and with that, a

valuable piece of history was lost. It would be another 400 years before

one hears of Vrindavani Vastra again.in 1904, Francis Younghusband,

a British Army Officer serving in India, led an expedition to Tibet. Among

the artifacts he took back to

Britain

were a few exquisitely woven �figured silk textiles� from Tibetan

monasteries. These silk tapestries were donated to museum in Britain in

1905 and for the next 85 years remained catalogued as �Tibetan Silk

Lampas�, as Tibet was their last known place of origin. This despite

the iconography on the textiles being clearly Hindu Indian far removed

from the Buddhism practiced in Tibet. Only in 1992, a British scholar

would identify the �Tibetan Silk Lampas� as Vrindavani Vastra.

Krishna Riboud was born

Krishna Roy in 1927, in Dhaka, her mother Ena Tagore being a niece of

Rabindra Nath Tagore. She went to America on a Scholarship to study in

Wellesley College. There she met and married Jean Riboud, a French

aristocrat and wealthy businessman. Together they traveled the world and

amassed a vast collection of paintings and objects d�art, Krishna Riboud�s

special interest being in Oriental Textile. In 1979, she founded the

�Association for the Study and Documentation of Asian Textiles� (AEDTA),

in Paris, to catalogue her collection. It had some 1600 items of Indian

textiles, dating from the end of the 15th century to the

present era. Among the Kashmiri Shwals, saries from Benaras

and Bengal, hand painted cloths, and religious hangings, are few very rare

in Assam half-damasks. In 1990, she offered 148 items out of her

collection to Musee Guimet in Paris. They are housed in a special

gallery in the museum as the Jean and Krishna Riboud collection. Two of

the exhibits of figured silk depict various avatars of Vishnu,

and Krishna�s

activities

in his childhood. Scholars have now determined them to be Vrindavani

Vastra.

As the images of the

Reboud collection gained currently in the art circles, it alerted Rosemary

Crill, Curator of the Indian Department of London�s Victoria & Albert (V &

A) Museum, to two exhibits of �Tibetan Silk Lampas� in the possession of

the V& A. By 1992, altogether 15 different specimens of tapestries of the

same type, described as �strikingly beautiful figured silk textiles�, had

been located in museums around the world: in the U.K., the U.S.A, France,

Italy, and in India�s Calico Museum in Ahmedabad. The term Vrindavani

Vastra, cloth of Vrindavan, is loosely used to describe this

group of tapestries.

The Vaishnavite

iconography, quality of silk, stylization of the drawing, dye analysis,

and the blocks of curious in woven script in the tapestries, first led

Rosemary Crill to Bishnupur in

West Bengal, a known centre for weaving. She had to discount

this theory when the designs appeared far removed from those on known

Bengali silk weavings. She then looked further east although it was

traditionally believed that there has never been any complex, high-quality

textile produced in the north-east except simple tribal weavings or

unadorned silk lengths.

Further research on art

of medieval Assam revealed that during the 1560s. Sankaradeva had offered

Prince Chilarai to oversee the weaving of a great silk scroll, depicting

the early life of

Krishna. A cloth named Vrindavani Vastra is

described there as woven with a large variety of coloured threads like red,

white, black, yellow, green etc.with in woven captions; this description

matched the design in the exhibits of �Tibetan Silk Lampas� in V & A

Museum. Rosemary Crill surmised that these �figured silk textile� must

represent a direct continuation of designs, and some may even be part of

the original vastra itself. Another piece housed in the museum of

Mankind, British Museum, London, revealed a song from Sankaradeva�s drama

Kaliya Daman, beginning with the words �geet raga asowari, awata

kal kali bariara�, in Assamese, an irrefutable evidence of its origin.

Interestingly, almost

all the tapestries have a Tibetan background. How they all got into Tibet

from Assam and why not a single specimen is now available in its place of

origin remain a mystery, as also how such a strong tradition disappeared

without a trace. The Tibetan connection is explained by the existence of a

centuries old and still thriving trade route through Bhutan, just north

Barpeta in Assam, Where the Vrindavani Vastra was woven. The

practice of barter between the merchants of Assam, Bhutan and Tibet was

common. Assamese merchant exchange silk, rice, skins and horns for silver and

salt from Lahasa. At the recent

British

Museum

exhibition �Between Tibet and Assam� affirmed, to this day, to have their

cymbals and their other religious paraphernalia made exclusively by

Assamese bell-metal craft man based in Sarthebari near Barpeta.

The 15 tapestries

differ in quality and design, and are surely not fragments from a single

larger piece. They may have been woven at different times and places other

than Barpeta but scholars agree that they all belong to the same school

and genre as that of Sankaradeva�s weavings. The use of complex weaving

technique such as Lampas indicates great technical skill on part of

weavers, and is strongly suggestive of an enduring tradition of long

standing. The evidence also dispels the nation that northeast India has

never been a centre for complex, high quality textile production.

Furthermore, it lends credence to the suggestion made by some scholars

that there once existed a thriving trade in silk between

Assam

and China.

History of medieval

Assam

records that nearly every household had knowledge of weaving and produced

fine clothes of cotton and silk. Professional weavers called Tantits

were settled at certain locations such as Tantikuchi, where the

Vrindavani Vastra was woven and the Barpeta Kirtana ghar now

stands. Sankaradeva, on return from his first pilgrimage (circa 1493), is

said to have organized a group of weavers to try new ideas and

innovations. Further, a mammoth task as the Vrindavani Vastra would

not be undertaken without trained weavers already at hand. As is the

practice with Assamese Vaishnavism, sacred texts are placed on the

altar in place of idols. These cloths are used to cover the altar and also

to wrap the text itself. Evidence suggests that over a period of time, the

elaborate and complex designs gave way to simplified, large scale,

repetitive motifs of today.

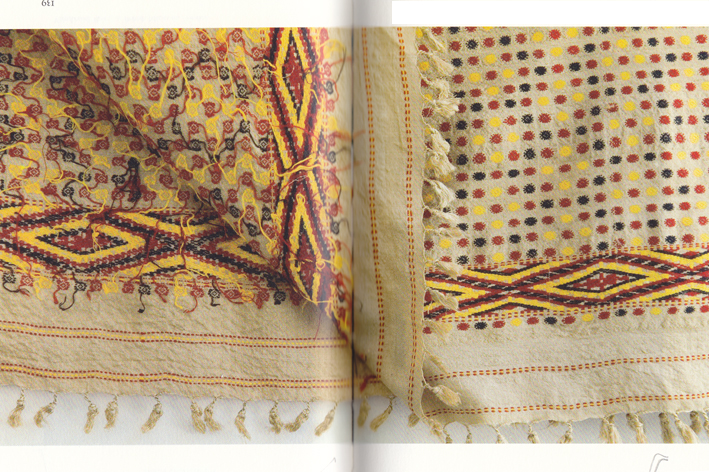

Of the 15 tapestries

identified so far, as 14 appear to have been woven in mid 17th

to early 18th century. While indicative of the tradition

persisting long after Sankardeva�s death, these 14 are ruled out from

being a part of the original Vrindavani Vastra. The only likely

contender for this distinction is a piece measuring 2 feet 8 inches by 7

feet 8 inches, now on display in Musee Guimet in Paris. Intended as

a �Gokhain Kapor� an altar cloth, it depicts various avatars

of Vishnu, the man-eagle Garuda, and Krishna playing the flute in

the branches of a tree. It is the finest and earliest of this group and

the date of around 1565-1569 is compatible with the style of drawing of

the period. However, lack of comparable physical evidence in its place of

origin, leaves the mystery unresolved.

Popular belief in Assam

has it that the tapestry now housed in the British Museum, Museum of Mankind,

London, is the or at least a part of the original Vrindavani Vastra

presented by Sankardeva to Chilarai in 1567-68. This belief has been

reinforced by it being so depicted in a recent (2010) Assamese film on the

saint. By far the largest of the fifteen known specimens, this vast

hanging consist of twelve silk lamps panels stitched together. Over nine

meters wide and nearly two meters long, this magnificent specimen was

taken from a monastery near Gyantse in

Tibet

by a member of the 1904 Younghusband expedition. The British Museum after

detailed study and technical analysis has dated it as of mid to late 17th

century, nearly a hundred years after the saint�s death. This was

confirmed in a public address by Richard Blurton, Curator of British

Museum, during his visit to Assam in late 2009. Furthermore, while Lampas

weaves were developed as 1000 A.D., its production began in earnest only

in late 17th century in Lyon, France. However, public sentiment

still holds sway over scientific evidence.

The innate quality of

these tapestries is evident as on 25 March 2004, Christie�s of New York,

the auctioneers, put on sale a piece of �figured silk from Assam� at a

reserve price of 1,20,000 US Dollars. More than four hundred years after

it was created, Vrindavani Vastra continues to weave its magic on a

timeless warp.

|