|

Last Days

Sankaradeva is 119 years of age. His religion is now firmly

in place, his life�s work done. His multifaceted genius lies bare;

remarkable in that he achieved it all while propagating his faith. The

great saint is ready for a journey beyond.

In February-March of the year 1568, Sankaradeva set sail

from Pat-bausi for Koch Behar, leaving his family and worldly concerns

behind. He broke journey at Ganakkuchi to spend the night with Madhavadeva.

They shared a meal and in their last intimate discussion, Sankaradeva is

said to have placed in the hands of his chief disciple the work he had

developed thus far.

Sankaradeva had given his all in furtherance of his

religion. Nevertheless, he cared deeply for his family. Uncompromising though

he was, he behaved in the manner typical of the domesticated husband within

the bounds of his home. He quietly tolerated his wife�s indulgence in

various cults and worship of idols. Only after Sankaradeva�s death was

Madhavadeva able to convert his preceptor�s wife to strict monotheism.

He married twice and raised five children. Like any other

parent, he was concerned about their welfare. Sankaradeva was pained when

his eldest son Ramananda was not much inclined towards religion. When he

showed little interest in his studies either, Sankaradeva devised a way to

inspire in him an interest in both. Sankaradeva had him trained in

Kaitheli, the art of transcribing manuscripts, and also in

account-keeping, a traditional occupation of the Kayastha people.

Ramananda would then earn the respect reserved for the literate, and also

make a living. To his credit, Ramananda became proficient in Kaitheli;

he also looked after the accounts of the Tantikuchi weavers.

Sankaradeva had hoped that if not his children, his

grandchildren would carry the tradition forward. So it came to be. Two of

his grandsons, Purusottam and Chaturbhuja, became preachers of note; their

descendants went on to establish xatras known as nati

(grandson) xatras. Chaturbhuja�s wife Kanaklata became the first

women preceptor in Assamese Vaishnavism. She would later resurrect Bardowa

xatra from its ruins,150 years after Sankaradeva had left it under

duress.

Arriving from Pat-bausi, Sankaradeva took up

residence at Bheladenga xatra in Koch Behar. After a short stay,

Sankaradeva became sick. The end was near. At his death-bed, a contrite

Ramananda, his eldest son, is said to have pleaded that Sankaradeva�s

inheritance be passed down to him. Sankaradeva advised him to contact his

mother for any of the earthly possessions. When Ramananda explained that

he meant Sankaradeva�s religious inheritance, the great saint

lapsed into silence. For, true to his democratic nature, Sankaradeva had

chosen his most capable and faithful disciple, Madhavadeva, as his

spiritual successor. Sankaradeva�s long and fortuitous journey came to an

end on Thursday,

21 September 1568.

Summing Up

To call Sankaradeva a mere religious reformer is misnomer.

His being a man of religion did not limit the scope of his universal

influence. The reforms he engendered pervaded every strand of social

milieu. He raised his people from a debased form of Sakta tantrism

to the monotheism of his Vaishnava faith. He achieved this not

through polemics or organized propaganda, not by decrying what was evil

but by presenting what was virtuous, in a manner that appealed to their

imagination. His religion brought in a profound change, a purer spiritual

life to Assamese society, and has held it together for more than 500

years.

Even those who do not subscribe to Sankaradeva�s precepts

and ideologies recognize in the context of their identity, their

language, dialects, thoughts and value judgments; the indelible

influence of Sankaradeva�s legacy. Museums in

London

and Now York, who know not of his verses, marvel at his creativity in a

completely different sphere; children in Assam, who have not seen the

Vrindavani Vastra, listen to his verses as a matter of course. Such is

the scope of his inspired reach, unaided by colonial interests and

unhampered by small ambitions.

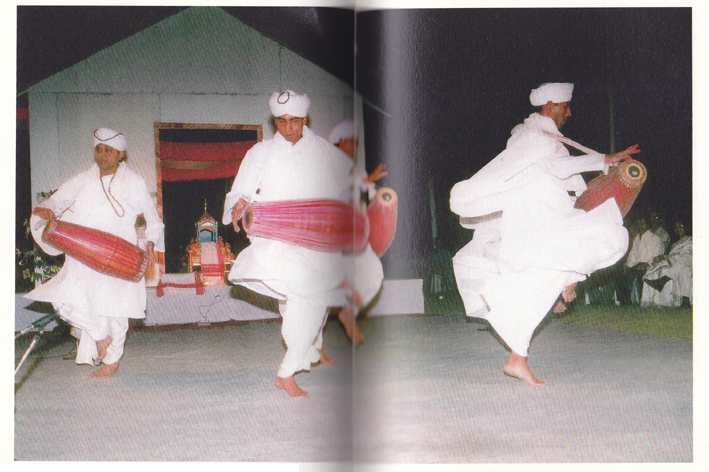

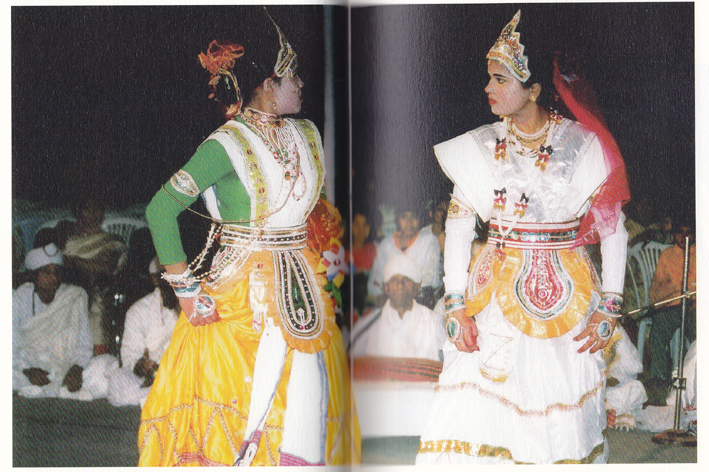

Sankaradeva embodied creativity; and above all, he was a

man of religion. His literary and artistic activities are not ends in

themselves; they are consciously oriented towards the sharing of his

creed. His work,be it a hymn, a verse for chanting, dramas for the

stage, dance forms, or even a drum for accompaniment, was only to draw

his audience to the word of God. That he performed each task with

consummate excellence is a measure of his greatness.

The India of Sankaradeva�s day had not yet come together as

one, as it would a few centuries later in its fight against colonialism.

It was a conglomeration of distinct regional identities: Kabir�s influence

touched the regions around present-day Uttar Pradesh and Guru Nanak�s the

Sikhs, Chaitanya�s words embraced

Bengal while Sankaradeva�s moved

Assam.

Dr. R. K. Dasgupta, the eminent scholar, writing on

Chaitanya and the Vaishnava movement in

Bengal, makes clear:

�It has now become important to know that Sankaradeva was thirty six years

old when Chaitanya was born and that Vaishnavism had struck deep roots in

Assam when the great leader of the new faith in Bengal had just begun his

work.� Scholars acknowledge: �If any religious leader and poet has

received much less attention than he deserves, he is Sankaradeva

(1449-1568),the founder of Assamese Vaishnavism and one of the finest

writers of devotional verse in Indian literature.�

The great are not guided by small ambitions. Many have

faith, only a few the courage to carry it through. Erasmus and Luther both

had faith; Luther along had the courage of conviction, as did Sankaradeva.

Some movements are fleeting, bright and glorious while they last.

Sankaradeva�s faith has stood the test of time, and half a millennium

later, shines brighter than ever. A wider reassessment dose not add to

that achievement. For it is clear he stands among Sankaracharya,

Ramanujacharya, Ramananda, Kabir, Chaitanya, Mira Bai, Guru Nanak and

Tulsidas.

|