Birth

Sankara

is born on an uneventful day in September of the year 1449. His father,

Kusumavara, is over-joyed; for, he had gone across the mighty river

Brahmaputra to Singari and prayed before Lord Shiva, seeking a

son. There is also quiet satisfaction for the Satyasandha,

Sankara�s mother. Finding her without child after several years of

marriage, Kusumavara had taken a second wife. By a turn of fate, it

is Satyasandha who now bore him his first child, a son much

coveted.

That night, there are great festivities in the household of

the Siromoni Bhuya in Alipukhuri, a small village near

Bardowa in Nowgong district in central

Assam. No one in

attendance would sense that the history of the period

would one day describe the Bhuyas as �petty chiefs�.

Ancestors

Sankara�s

ancestors entered Assam around 1350 through the western route, as

emissaries from Dharmanarayana of Gaur to the Kamata king

Durlabhanarayana. Durlabhanarayana settled them with land and

men, and the title Bhuya. Bhuya, also Bhuiya or

Bhuiyan, was merely the Sanskrit equivalent of the Persian word

�Zamindar�, meaning landlord, and had nothing to do

with caste. Each Bhuya was independent of the others within his own

domain, but they joined forces when threatened by a common enemy.

Chandivara, the ablest among them, was made their leader. A man of

enterprise, he was as well versed in the scriptures as in the art of

warfare. He earned the goodwill of the Kamata king when he

outsmarted a scholar from Nadia,

Bengal, in a debate in

the royal court.

Chandivara

and few other Bhuyas later moved east and finally settled at

Bardowa in Central Assam, ruling individual principalities or tracts

of land. Being their leader, Chandivara held the title �Siromoni

Bhuya�, meaning overload or holding supremacy over many Bhuyas.

The tradition of learning continued through the generations. Sankara�s

father, Chandivara�s great-grandson Kusumavara, would come

to be known in his time as a scholar of some repute. When Sankara

lost his parents while very young, his grandmother would see to it that

the boy followed the tradition of his forefathers.

Assam on Its Own

The only routes between

India and the rest of

the world, practicable for mass migration, lie to its northwest

and northeast confines-hemmed in as it is by a sea to its

south, and the lofty

Himalayas to its north. Over the centuries, invaders such as the

Greeks, the Huns, the Pathans and the Mughals entered

through the northwestern route. Via the northeast came successive hordes

of invaders from

Burma and Western

China. By the thirteenth century, northeastern India including Assam

became a conglomeration of tribes of Mongolian

origin, and the border was virtually sealed.

As the Buddhist scholar Richard Salomon points out,

Assam�s historical

tradition-like that of

India�s

neighbors Bhutan, Tibet and Sri Lanka- predates that of the rest of India

by a good few centuries. This is because the Ahoms of the Tai

or Shan race, who invaded Assam in 1228 and ruled uninterrupted for

nearly 600 years, brought with them a keen sense of history. Their

buranjis, or historical chronicles, give a full and detailed account

of their rule since its inception. In the Ahom language, bu

is an �ignorant person�, ran is �to teach� and ji is

�granary�; thus buranji means �a store that teaches the ignorant�.

Bansabalis

or family histories, maintained by other kings and nobles of the period in

Assam, also provide some detail of contemporaneous events. Unfortunately,

these histories remained inclusive and sometimes in private preserve. The

19th century historian Edward Gait would employ an Assamese

youth to delve into these chronicles for the purposes of his research.Elsewhere in India, the tradition took hold after the arrival of the

Mughals in 1526.

For events of earlier dates, historians painstakingly

pieced together information gathered from old inscriptions, accounts of

foreign invaders or travelers, and incidental references in religious

writings.

Assam is geographically

so situated that interaction with the rest of the country was possible

only through its western border. Land communication at the time was not

easy, while river navigation prospered after the British took over in the

early nineteenth century. The Assamese perceived a need for protection of

their western border from foreign invaders, and set about ensuring

it, inadvertently bringing on a certain degree of insularity.

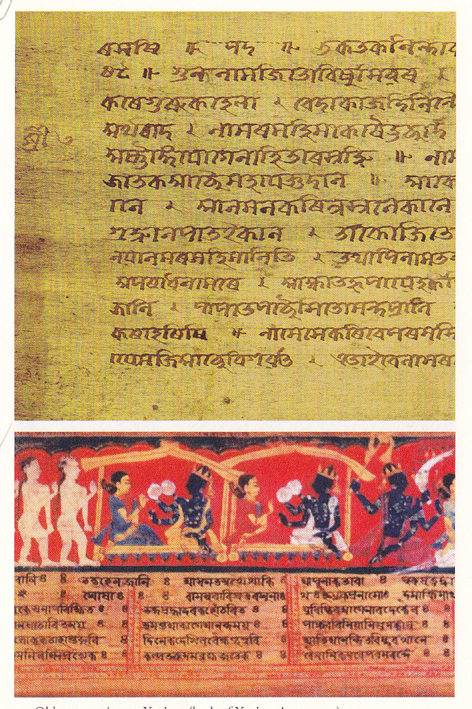

As with traditional scribes across civilizations,

transcription and record keeping in

Assam were largely

confined to the courts. And so, despite the presence of chronicles, there

are few contemporary accounts of ex-regal events in the time of

Sankaradeva. Of his four generally accepted biographies, the earliest

is by one who was a mere child when Sankaradeva passed away in

1568; the others written in early to mid 17th century, long

after his death, are not always of the highest reliability.

Furthermore, the biographies tend towards hagiography,

bringing in the pan-Indian tradition of myths and miracles that glorify

saints. This makes any account of the saint�s life controversial

especially where dates are concerned. What is of relevance, however, is

the body of his work that clearly brings out the substance of it.

His Times

In mid-15th century, the northeastern states are

ruled by a multitude of heterogeneous entities. The Koch and the Kamata

kingdoms are in the west, the Jaintias to the south, the

Chutiyas to the east mainly on the northern bank of the river

Brahmaputra,

and the Kacharis and the Ahoms to the east on its southern

bank. In between, a few Bodo tribes enjoy a precarious existence as

do a number of Bhuyas. Clearly, the once powerful Bhuyas,

Sankara�s ancestors, who had arrived in the 1350, are on the decline.

The Ahoms, who entered

Assam

in 1228, are by far the most dominant power. The whims of the Ahom

king of the day would greatly sway the fortunes of Assamese Vaishnavism.

In 1497, Suhungmung became the first Ahom king to assume the

Hindu name, Swarga Narayan or Swarga Dev, signaling his

desire to merge with the mainstream. It also meant ascending influence for

the Brahmin priests, the fiercest opponents to Sankara�s creed. The

beleaguered preacher would seek succour in the neighbouring Koch

kingdom of

Naranarayana.

The rest of the Indian subcontinent is a mosaic of regional

kingdoms: the princely states of Vijayanagar (1336-1646) and Mysore

(1399-1947) in the south, the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) in the North,

the Islamic Sultanates (1206-1596), Deccan Sultanates (1490-1686) and

other small states else where. The Mughals who would dominate most of the

northern parts of the subcontinent arrive in 1526, bringing with them

Islamic art, architecture and a keen sense of history.

Elsewhere in the world, the Incas (1200-1573) in

Peru are in their full

glory, the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922) flourishes in present-day

Turkey,

and in China the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) reigns supreme. Elizabeth of

England ascends the throne in 1558 while, in 1547, Ivan the Terrible

becomes the first Tsar of Russia. The renaissance in Italy, secured by

patronage of both the church and the crown, is in full bloom.

Described as a resurgence of learning from classical

sources, the renaissance becomes the bridge between the middle ages and

the modern era. Scholars scour monasteries looking for ancient manuscripts

and begin rewriting history. In

England, Henry VI

founds King�s College in Cambridge (1441), while Oxford (circa 1167)

---the oldest University in the English-speaking world---changes from the

medieval Scholastic method of teaching to the Renaissance education.

Christopher Columbus sets sail in 1492 to discover America, and in 1498

Vasco da Gama finds the spice route for trade with India. In the sphere of

religion, a period of extreme decadence leads to rumblings of discontent

within the Roman Catholic Church.

The dissidence that began with John Wycliffe (1320-1384),

the English theologian, now becomes more vocal. Desiderius Erasmus

(1466-1536), the Dutch Renaissance humanist, criticizes clerical abuse in

his writings but remains committed to reforming it from within. Martin

Luther (1483-1546), the German monk, goes a step further. In 1517, in open

defiance of papal authority, he launches the Protestant Reformation.

Luther drafts a �Letter of protestation� containing

these, and posts it on the door of the church. He denounces, among other

things, the Church�s practice of selling �forgiveness� for a price,

proclaims the Bible to be the only source of divinely revealed knowledge,

translates it into the language of the people and not into Latin, marries a

lapsed nun, and declares Protestant monks free to wed if they so choose.

He writes hymns for singing in the church, and his writings foster the

development of a popular German language.

This is in keeping with the pattern already evident in

other parts of the world, revealing phase of religious decadence followed

by reformation. One only needs substitute the Bible with the �Bhagawata�,

and Latin with �Sanskrit� to discern uncanny similarities in the ways of

the German monk with the neo-Vaishnava movement sweeping India, set in

motion by a handful of religious figures.

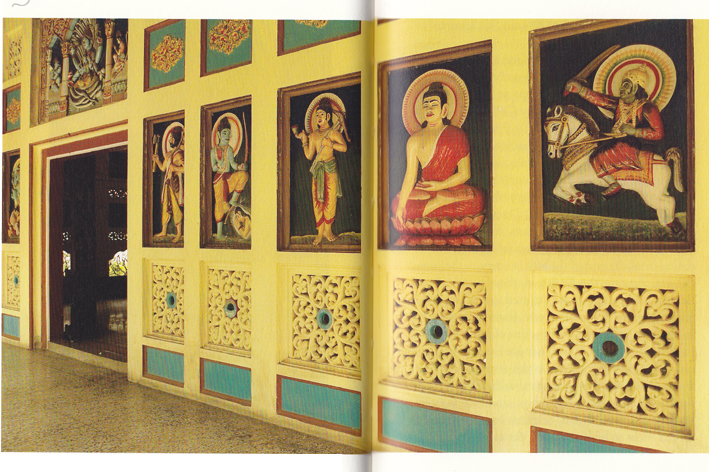

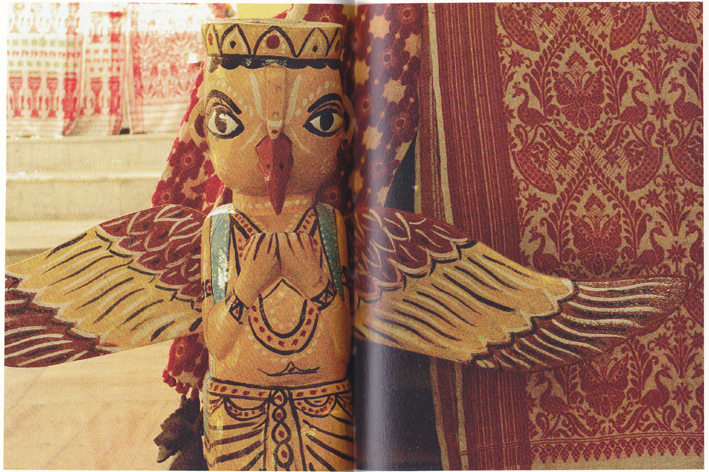

The three functions of the cosmos, creation, preservation

and destruction, are personified in Brahma, the creator, Vishnu the

preserver, and Shiva the destroyer or transformer. The Bhagawata Purana,

one of India�s

revered ancient texts, explains that the greatest benefit can be had from

Vishnu, called the �All-pervading one� or �one who is present everywhere.

In vaishnavite tradition, Vishnu is the Supreme God, worshipped

either directly or in one of his ten avatars, principally�Rama,

Krishna, Narayana, or Vasudeva. His followers are

called Vaishnava(s) or Vaishnavites while the

word Vaishnavism entered the English language in the nineteenth

century.

The worship of Vishnu in ancient

India is well

documented; it finds mention in the Mahabharata, in an episode later to

become the source of Bhagawad Gita. It flourished during the reign

of Chandragupta II (circa 375-413), and in Shaivite South

India, in 6th to 9th century, through the tireless

efforts of the twelve Alvar saints of Tamil Nadu. The seed of

Vaishnavism sown by the Alvar saints and nurtured by later

saints like Ramanuja (1017-1137) of Tamil Nadu, Basava

(1106-1167) of Karnataka and Namdeva (1270-1350) of

Maharashtra

is now in fruition.

As if by divine providence, from across India, a number of

religious leaders of great endowment appear on the horizon, bearing the

message of bhakti to the people: Ramananda of Allahabad

, Kabir from Varanasi, Sankaradeva in Assam

, Nanak in Lahore , Vallabhacharya of the Telegu

community in the South , Chaitanya of Bengal ,

Mira Bai from Rajsthan and Tulsidas from

Rajapur in Uttar Pradesh.

It is a period of tolerance among the diverse faiths.

Chistiyya Sufi saints of

Ajmer in Rajasthan invoke ideas from the Hindu bhakti

movement in their devotional songs. The Sikh holy book puts in its pages

thoughts from Hindu and Muslim saints: sixty one of Namdeva�s

hymns, one of Ramananda�s poems, and more than five hundred verses

of Kabir, one of the 99 names of God in the Islamic faith, find

place in the Guru Granth Sahib. This resurgence in the

universal and liberal doctrine of bhakti ushers in an era of

profound reformation in the socio-religious milieu across the country.

In such times, Sankara is born.

Aimless wanderer

Sankara losses his father at

the age of seven, his mother shortly thereafter, and is raised by his

grandmother, Khersuti. Indulgent towards her foundling, she lets

him wander freely for the first twelve years of his life. A happy,

carefree child, he spends his time grazing cattle and roaming the fields.

He goes hunting birds, deer, tortoises and porpoises, only to release them

unharmed, and often swims the mighty Brahmaputra across and back

unaided. He also indulges in the usual games played by village children,

such as ghila, kotora, bhatta and dugdugali.

This aimless wanderer would one day:

Found a religious order that would bring about a social

reform and over five centuries, become a way of life for his people.

Establish institutions that would become focuses of

Assamese art and culture.

Write with equal dexterity in three languages to leave

behind a treasure trove of literature, more than many religious poets of

the world have done.

Translate scriptures and epics from Sanskrit into idiomatic

Assamese to bring them within reach of the common people.

Compose soulful lyrics, set them to music in classical

pan-Indian ragas and sing them.

Create dramas, design costumes and musical instruments,

stage plays and also anchor them.

Evolve a dance form that would survive five centuries to

become one of

India�s

eight classical dance traditions, the only one that can be traced back

directly to an individual.

While doing so, he would find not only the ways but also

the means. One can only say that things come naturally to a

Mahapurusha (Great Man) as Sankara, soon to be adorned with the

epithet �deva�, would be known.

Days at School

Sankara�s

idyllic existence ended when his grandmother decided that playtime was

over and formal learning must begin. He would attend a tol or

chhatrasala, a pan-Indian educational institution, run by Brahman

scholars. Tols had small cottages for students hailing from afar.

The pupils also had to clean and sweep the school premises and keep them

in order.

The curriculum of a tol consisted mainly of Sanskrit

grammar, lexicon, the epics, the puranas and other religious works.

Accurate copying of original religious texts and reading them to scholars

or holy men were considered qualifications in themselves. Scholars from

outside visited such institutions and held discourses. After completing

education in a local tol, many proceeded for further studies to places

like Varanasi,

Mithila and

Nadia.

One�s learning was put to further rest in an open assembly

of pandits, sometimes in the presence of royals. Scholars partook

in verbal duels in such assemblies to display their learning or to settle

contentious issues. A win, especially in a royal court, earned the

victor great accolade, as with Chandivara, Sankara�s ancestor. In

years to come, Sankara�s debating skill would come to his aid on

many occasions.

On an auspicious day, the twelve-year-old Sankara

set foot in the tol of Mahendra Kandali, a Brahman pandit.

The boy took time to adjust to the cloistered regime but soon became a

devoted student. About Sankara�s courses of study, one account

gives an exhaustive list of subjects and works covering all branches of

Indian learning---the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Ramayana, the

Mahabharata, the puranas, the sambitas, the tantras,

grammar, lexicon and the kavyas. Another mentions only chapter on

grammar, adding that Sankara studies all books without exception

and became an unerring scholar.

Evidence of this is borne out by Sankara composing

his first poem soon after joining school. An ode to Lord Vishnu, it

uses only the consonants and Vowel �a� � whatever Sankara had been

taught thus far.

The eight-line poem begins with hands lifted to the

heavens,

�karatala kamala

kamaladala nayana,

bhavadava dahana

Ghana vana saiyana.

(�Thy palm is like the lotus, Thine eyes like lotus

petals, Thou art the consumer of worldly afflictions, Thou art the sleeper

in deep forest.�)

And ends with a note of submission:

jagadaha mapahara

bhavabhoya tarana,

parapada layakara

kamalaja nayana.

(�Thou art the saviour from the earthly grief; Thou

art the giver of final beatitude; O Lotus-eyed Lord! I worship thee.�)

Vibrant with unmistakable stirrings of the sentiment of

bhakti, or devotion, the poem is a portent of things to come. Its

lyrical beauty and sobriety of thought, coming from one so young,

astounded Mahendra Kandali. The teacher had another surprise

coming.

One day, Kandali found Sankara asleep in the

school grounds, the extended hood of a cobra protecting his head from the

burning rays of the sun. With this epiphany, the guru saw his young

pupil�s future greatness. He conferred on him the epithet �deva�,

usually applicable to Brahmans, and asked other pupils to address him as

Sankaradeva, not Sankara. Kandali also exempted him from the

ordinary student�s duty of cleaning the school precincts.

By the age of twenty, Sankara had completed all

course of study assigned to him by his teacher. He had come to Yoga at

about fifteen years of age and practiced it with great diligence, becoming

immersed in matters of spiritual subtlety. It is said that when Sankara

left school, everyone, above all his teacher Mahendra Kandali,

recognized his immense learning and saw in it his future greatness.

Sankaradeva,

true to his nature, would first pay his dues to his ancestors.

Marriage and

Bereavement

Sankaradeva

assumed the administrative duties of the Siromoni Bhuya.

These had been temporarily assigned, after his father�s death, to the care

of Jayanta-dalai and Madhava-dalai, his father�s paternal

uncles. He began looking after the welfare of his people, mainly farmers

and tradesmen.He had to contend with the frequent territorial disputes

with the Kacharis who owned farmland contiguous to the Bhuyas.

Skirmishes would often occur, keeping the neighbours in a state of

constant agitation. The Bhuyas, by then, had become militarily weak

while the Kacharis had grown stronger. Sankaradeva used

resources at hand to resolve conflicts amicably before they came to a

head, and generally succeeded.

Sankaradeva

was twenty-one and his people suggested marriage for him. He married

Suryavati, the fourteen-year-old daughter of Harivaragiri, a

wealthy Bhuya. After few years of marriage, Suryavati gave

birth to a daughter, named Manu or Haripriya. Tragedy struck a year

later; Sankaradeva, who had been orphaned at a tender age, now lost

his wife. At twenty-four years of age, his mind was distracted once more

by personal bereavement.His life now took a turn, in a manner first

evident during his aimless wanderings.

The world around Sankaradeva, late 15th

century Assam,

was in a state of flux. There was constant fighting among the

heterogeneous entities, jostling for power and territory. From the west

came successive invasion from other expansionist forces. Hemmed in between

several kingdoms, the Bhuyas were plagued by wars not of their

making, made worse by their lack of military strength. Sankaradeva

was a witness, as a result, to great many wars during his lifetime.

The Ahoms would fight five wars with the Kacharis,

ten with the various Naga tribes, seven with the Chutiyas,

and engage in numerous conflicts with other minor entities. One Ahom king�Suhungmung�would

be murdered by his power�hungry son. The Mohammedans would invade three

times, once destroying the pre-historic temple at Kamakhya. Growing

ambitious, the Koch King would wage wars with the Kacharis, the

Manipuri Raja, Jaintia, Tippera and Sylhet kings, and the

Badshah of Gaur, besides attacking the Ahoms five times.They are

battles for greater glory, never greater good; involving the wagering of

lands and the wasting of lives.

.

When it came to religion, the intrigues were no less

bitter, the means no more redeeming. Sankaradeva, who would one-day

bar idolatry from his religion, had himself grown up in a practicing

Sakta environment. His great-great-grandfather Chandivara, a

devout Sakta, bore the epithet �Devidasa� (servant of the

Goddess). His father, Kusumavara, kept and image of the goddess

Chandi in the house for worship. Sankaradeva was born after his

father had offered prayers to Lord Shiva, and had been named, at birth,

Sankara-vara (gift of Sankara, another name for Lord Shiva).In the hands of unscrupulous practitioners, however, Saktism had by

then degenerated into a debased form of faith.

Gait describes

Assam at this time: �Saktism

was the predominant form of Hinduism. Its adherents based their

observances on the Tantras, a series of religious works in which

the various ceremonies, prayers and incantations are prescribed, a

religion of bloody sacrifices from which even human beings were not

exempt.� Self-serving priests encouraged ritualistic worship of gods and

goddess, and prescribed votive sacrifice of animals. This disturbed the

young Sankaradeva, his intellectual awareness kindled by formal

education under Mahendra Kandali. Sankaradeva saw around him a

singular lack of tolerance, goodwill, and fellow-feeling. There was

nothing beyond greed and selfish ego. Above all, there was lack of

Bhakti as propounded in the Vedas and the Puranas.

When Sankaradeva�s teacher felt he had no more to

offer, Sankaradeva had left school. Burdened with the duties of an

administrator and a householder, he had continued his scholarly pursuits

on his own. He immersed himself in the scriptures, held religious

discussions among his people and engaged in discourses with visiting

scholars. Even as a young cowherd, seemingly aimless in his wanderings, he

had an astute sensitivity to his surroundings. Once free of the routine of

school, he brought that sensitivity to bear on his independent study.

The neo-Vaishnava movement, unfolding across

India, acted as a spark

to this spirit. The understanding and commitment of the young

Sankaradeva, working alone in a small village away from all centres of

mainstream security, was of a piece with the movement. The outline of his

work secure in his mind, Sankaradeva was now ready for a journey

out, to meet and engage with other like-minded scholars.

Worldly obligations would delay his departure.

First Pilgrimage

Sankaradeva

waited a few years. When his daughter turned nine, in keeping with the

temper of the times, he gave her in marriage to a Kayastha youth

named Hari. He entrusted the household duties to his son-in-law,

and administration, as before, to Jayanta-dalai and Madhava-dalai.

In 1481, the 32 year-old Sankaradeva set out on his first

pilgrimage. He was accompanied by seventeen others, including Mahendra

Kandali, his teacher. The pilgrimage would last twelve long years, a

fair indication of Sankaradeva�s belief in the need for rigorous

inquiry and debate in the making of a robust faith.

Sankaradeva

visited the key centres of religious importance in various parts of the

country, especially those connected with the lives of Rama and

Krishna. Puri with the 12th century

temple of Lord

Jagannath was of special interest to him, and he stayed there the

longest. Puri was the confluence where religious scholars gathered

to exchange ideas, propound new thoughts and engage in debates.

Sankaradeva�s personal surrender to the concepts of sadhana and

bhakti�spiritual practice and devotion-resonated with the neo-Vaishnava

movement. Holding discourses with scholars from around the country, all

proponents of the gospel of bhakti, Sankaradeva refined his own

faith.

Sankaradeva

found bhakti pouring out in devotional songs, as he heard men of

faith sing the songs of poets in Puri and

Varanasi. He was witness to the power of community singing.

At Badarikasrama, one of the scared sources of the Ganges,

Sankaradeva was moved to compose his first devotional song. Written in

Assamese Brajabuli, a linguistic construct comprising Assamese and

Maithili, the hymn begins with the words �mana meri rama

charanhi lagu� (rest, my mind, rest on the feet of Rama) and is

set to raga Dhaneshri.

Brajabuli

made popular by the 14th century poet Vidypati, was

used by poets in Northern India particularly to narrate songs on the theme

of Radha Krishna. Rabindranath Tagore would write his

�Bhansingha Thakurer Padavali� in Brajabuli in 1884. In

composing his hymn in Brajabuli and setting the tune to a raga,

Sankaradeva�s approach was pan-Indian.

Sankaradeva

returns home with a faith robust and secure.

Return Home

Sankaradeva�s

outlook on life was now much broader, and his religious beliefs

encompassed a wider horizon. He felt ready to propagate his liberal faith

of Bhakti among the people. However, his kinfolk insisted on his

marrying a second time and resuming the duties of the Siromoni Bhuya.

He yielded to the first and at the age of forty-eight, took as his second

wife Kandali, daughter of Kalika Bhuya. He declined the

administrative duties, declaring his intention to lead a life of devotion

and prayer instead.

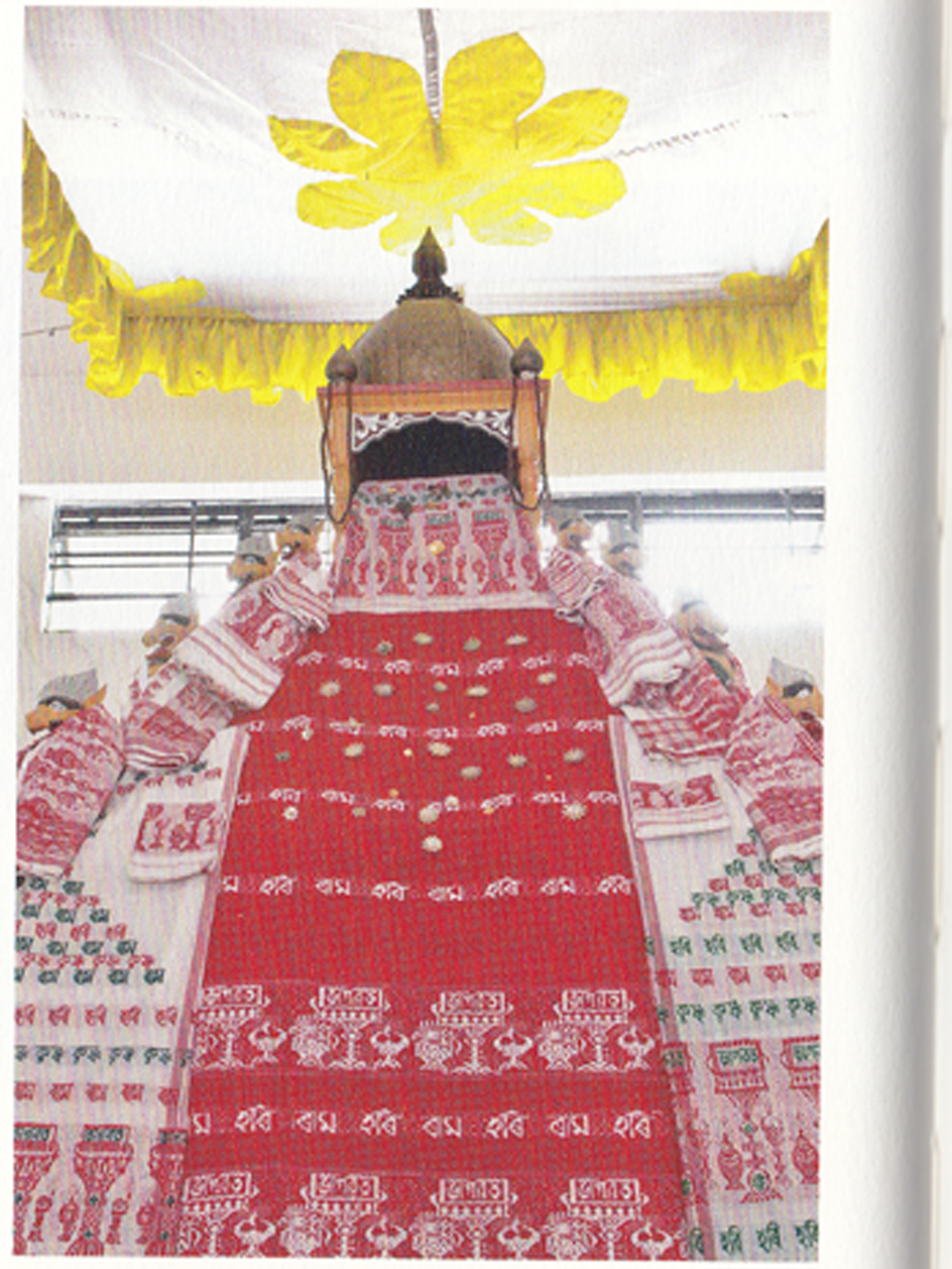

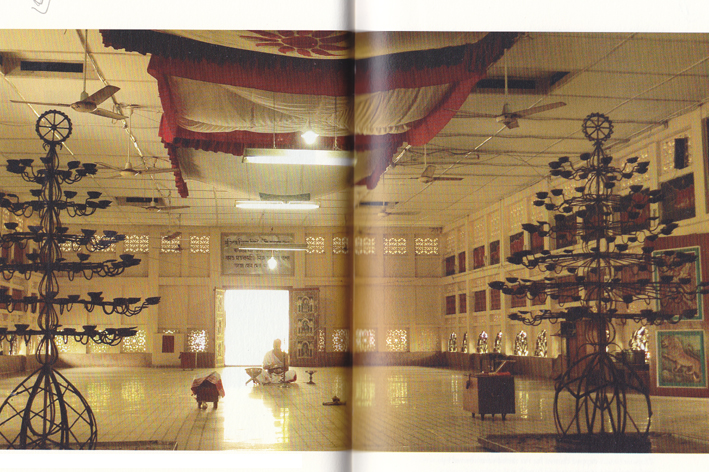

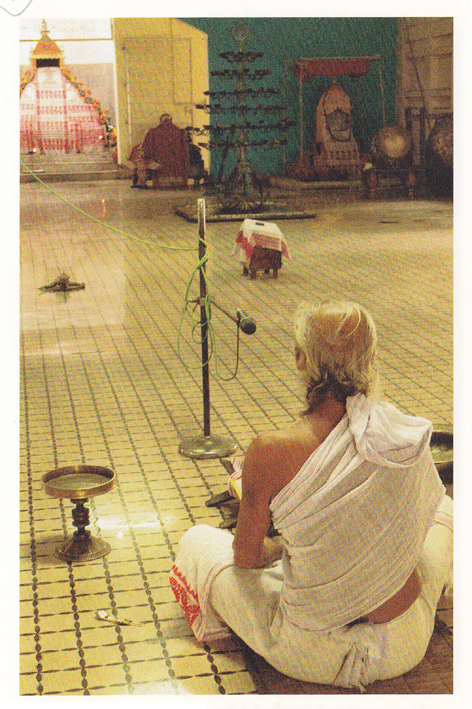

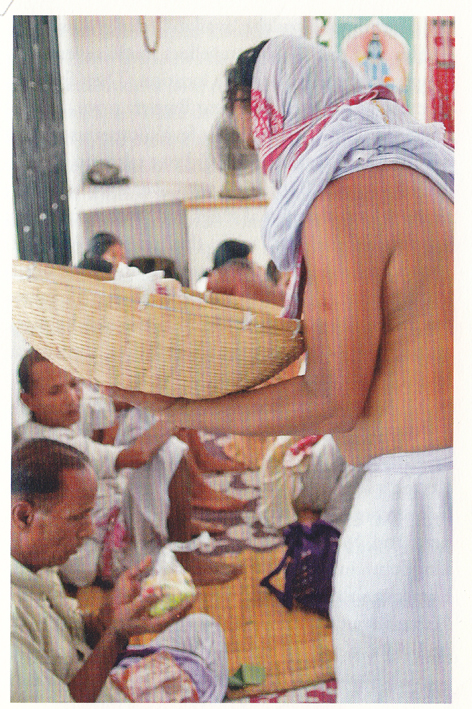

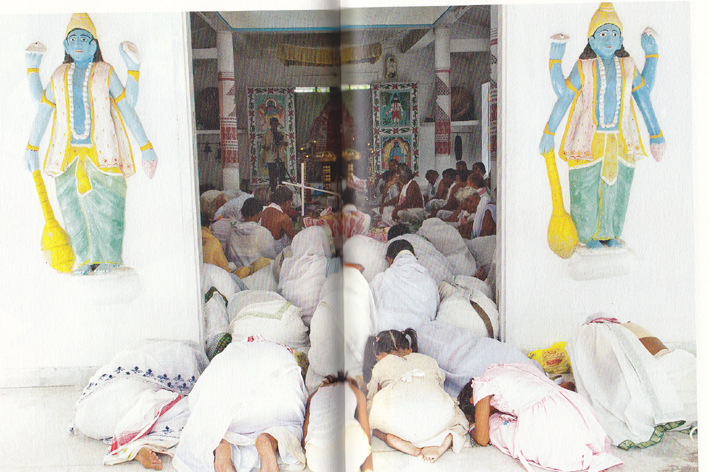

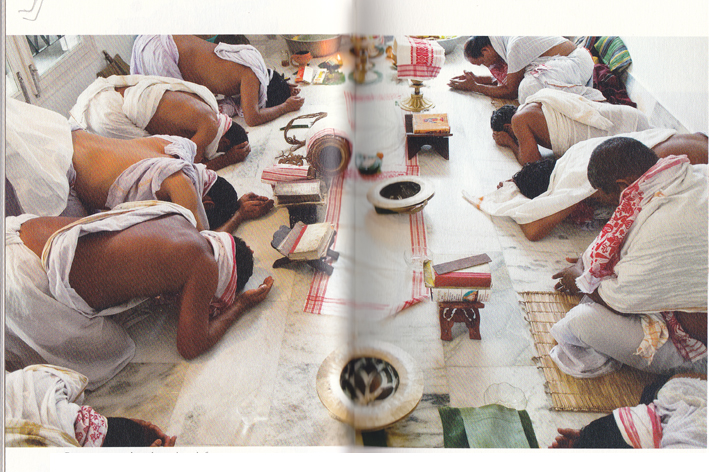

Sankaradeva

had a simple temple of thatched roof built for little away from the

householders, and immersed himself in the study of scriptures and in

religious discussions. Termed Hari griha or deva griha,

meaning house of the Lord, this would be the precursor to the naam ghar,

or prayer hall, as we know today.

Once settled in Bardowa, he was urged by the local

community to organize some kind of festivity as he must have seen during

his travels. So, one Poornima (full-moon night), in the month of

Phal guna (February-March), he organized at Bardowa a

Doljatra, a festival of colour. Known variously as Dol Poornima,

Dol Utsav, or Holi, it is observed with much gaiety,

particularly in

Northern India,

and is said to mark the day Lord Krishna professed his love for his

consort Radha. The festival was a great success. Doljatra

today is an annual event celebrated with great fanfare, especially in

Barpeta xatra; the one held in Majuli draws visitors from

around the world. Some accounts, however, place Sankaradeva�s

celebration of Doljatra at Bardowa at a date before his

first pilgrimage.

Sankaradeva

next staged at Bardowa �chihna yatra�, a�dramatic presentation with

paintings� using seven hand-painted scenes in succession, each depicting

one of the seven Vaikunthas, celestial abodes of God, as the

backdrop. This dramatic exercise was written, produced, and staged by

Sankaradeva with music, illuminations and fireworks. Sankaradeva

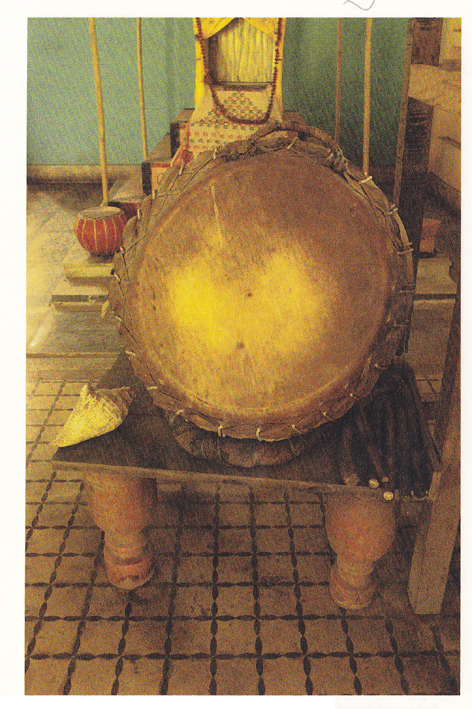

also played the main part of Sutradhar, the anchor. For the

occasion, he had musical instruments such as drum and cymbals specially

made to his design.

It was a tremendous success. His old teacher Mahendra

Kandali was overwhelmed by his pupil�s achievement. He turned away

when the latter came to pay him his respects, saying Sankaradeva

was now his guru. It clearly was the beginning of what would later become

the Ankiya Nat. Chihna yatra� is said to be the first modern drama

in the Indo-Aryan languages staged anywhere in the world, but this claim

cannot be substantiated as the next of the play has not been found. Again,

some accounts place Sankaradeva�s enactment of �chihna yatra�

at a time when he was nineteen years of age, long before his first

pilgrimage. Interestingly, it would by another eighty years before the

first �Early Modern English Drama� is staged in

London

in 1576.

Sensing the positive impact of audio and audio-visual

elements upon the masses, Sankaradeva set about exploiting it to

the full. A devotional song, a spectacle of high melodrama, a homely verse

for community chanting, a dance portraying the life of the Lord---would

all become vehicles for propagation of his faith.

A� fruit in full flower� was soon to come his way.

�Fruit in Full Flower�

Among the eighteen puranas, traditionally believed

to have been written by the ancient sage Vyasa, Bhagawata Purana is

the most celebrated and revered. I am said that one can attain salvation

by worshipping, listening to, and reading or even by looking at his sacred

book. Sridhara Swami, an Advaita (non-dualist) scholar,

describes this purana as �delicious fruit falling to earth through the

mouth of suka�, the narrator-son of Vyasa. As per accounts,

sometime after the first pilgrimage, one Jagadisa Misra arrived

from Puri bearing this �fruit� for Sankaradeva, complete with

commentary by Sridhara Swami. Jagadisa recited and explained

the whole work to Sankaradeva, which reportedly took, about a year.

Sankaradeva

was now convinced that this work was without peer. To him, the

Bhagawata Purana�s privileging of

Krishna as the sole worshipful, the imperative of taking

single-minded refuge in him, and the celebrating of his acts in the

company of holymen were sacrosanct. Sankaradeva proceeded to

immerse himself in the purana, setting himself the task of

propounding and propagating the cult of bhakti. Driven by an astute

awareness of universalizing power of hymns, he first composed verses and

hymns in simple Assamese. When his verses found ready an enthusiastic

acceptance from the masses, he extended his range of literary activity.

Sankaradeva�s engagement with the Bhagawata Purana,

complete with commentary by Sridhara Swami, proved to be a

galvanizing moment in his life.

Social reform was Sankaradeva�s main agenda; his

religion, a means for his people to climb out of the abyss they found

themselves in. He knew the faith needed to be liberal, practical,

universal, and accessible. Above all, it had to appeal to the audience it

was aimed at. Mere issuing of doctrinal messages was not enough; one had

to create the ways and means to carry it to the people. For it to be

successful, it needed to be administered with kindness, aberrations dealt

with firmly.

The oneness of the Ultimate Sprit had been the governing

ideal of most branches of Hinduism. Sankaradeva�s faith was no

exception; it was based on-

Eka deva eka seva

Eka bine nahi kewa

One God, one devotion,

There is none but One.

He called it eka sarana nama dharma, that is, the

religion of supreme devotional surrender to the One, the One being Krishna

or one of his incarnations.Out of the nine modes of bhakti,

enumerated in Bhagawata Purana, Sankaradeva chose two: sravana,

the act of listening to accounts of Vishnu, and kirtana, the act of

chanting prayers to the Lord. Simple singing of and listening to tales

of Vishnu or Krishna, and taking refuge in Him without any desire or

motive, were enough. �God is accessible neither through penance and

renunciation, nor through gifts. He is not accessible through yoga or

knowledge; He is tied down to bhakti alone.�

Sankaradeva�s

religion was democratic in nature, open to all, irrespective of caste or

creed. He declared that �to obtain final release or come to the presence

of God, one need neither be a Brahman, nor a sage, nor should one know all

the scriptures.� He embraced into his fold people of all denominations:

the Mikirs, the Misings, the Garos, the Bhutiyas and

the Bodos as well as a Kayastha, a Kachari, a

Chutiya, a Kaivartya, an Ahom, a Brahman, koch, a

Chandal (scavenger), and also people of other faith like

Chandsai, a Muslim, who reportedly became a much respected devotee and

rose in the ranks. To Sankaradeva, asceticism was not essential

for leading a spiritual life.

Sankaradeva

forbade the worship of other gods and goddesses in no uncertain terms.

�You will worship only Vasudeva and no other god. All worship is to

be found in the worship of

Krishna; God will not accept any other. Do not become His enemy by

violating religious rules. Do not enter their temples. Look not at their

idols nor eat their Prasad. Bhakti will be vitiated by such

practices.He warned the unbeliever, the frail of faith: �Those who

worship other gods and goddesses are worse sinners than those who kill and

eat dogs. There are no greater sinners than these.�

Seemingly harsh and intolerant, such strict disciplinarian

measures were designed to negate the mindless rituals associated with

idolatry, and to keep the motley flock together. A practical reformer,

Sankaradeva had his feet firmly on the ground; his sure understanding

of human psychology one of his greatest strengths. He once allowed an idol

of Lord Jagannath inside the kirtana ghar, leaving a canny

door ajar for Brahmans to embrace his religion. Five hundred years of

history would prove him right.

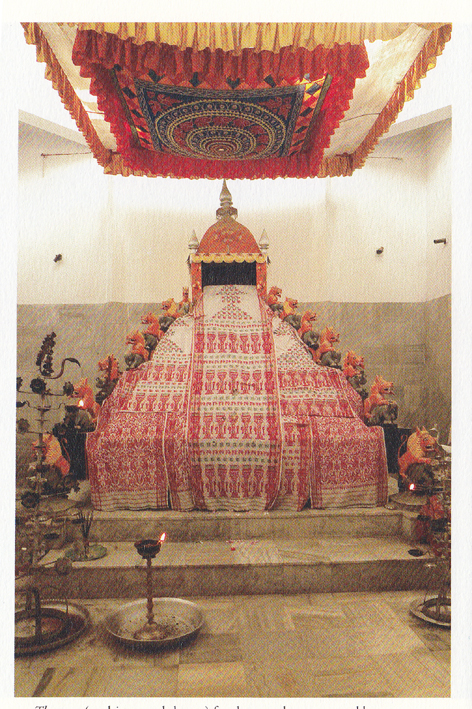

Sankaradeva�s

worship was austere, with the Bhagawata (or its concise version the

Gunamala) replacing all idols. Lord Krishna is said to have

invested his complete energy into the Bhagawata Purana, and this

work, therefore, was the perceptible image of Hari in worded form.

In place of an idol, the Bhagawata or its renderings were to be

reverentially treated as the Lord. Sankaradeva initiated his

disciples into his faith with the Bhagawata representing the Lord,

in whom the initiate�s soul would find refuge. In a similar manner, the

Sikhs worship the Adi Granth complied in 1604 by fifth Guru

Arjun Das; and the Terapanthi Jains Worship Scriptures, not

idols.

Sankaradeva�s

new discipline of faith in a single Divinity offered something simple and

straightforward, divested of all questionable associations or

implications. He defined the nature of the relationship between Vishnu or

Krishna and the devotee as one between the Lord and his servant.

It was the path of a man�s direct faith in his Master, without his

assuming the nature of a woman as in the Vaishnavism of Bengal.

Sankaradeva, ever mindful of the erotic overtones of Krishna-gopi

episodes, would not allow any form of eroticism in his faith, not even as

an allegory of divine love.

Sankaradeva�s eka

sarana nama dharma

is also called Mahapurushiya dharma. Both Sankaradeva and

his chief disciple Madhavadeva are considered to be Mahapurushas,

great beings further elevated by virtue of their faith in God, not by

birth.

Bolstered by the success of �chihna yatra�,

Sankaradeva declared himself a preacher and made his first

conversions. Jayanta-dalai�s wife is said to be the first convert,

followed by a leper, Harirama, later called Tulsirama. His

teacher Mahendra Kandali and friend Ramarama, also belonged

to his first batch of converts. Sankaradeva began traveling far

and wide to propagate his faith. He established kirtana ghar or

naam ghar--- a hall for congregational prayer�which became a popular

institution in the religious life of the Assamese people. He translated

religious texts from Sanskrit verse form into homely Assamese, wrote

devotional songs, and created music, drama and dance-forms as means of

reaching out to the people.

Sankaradeva

loved his birthplace. A much-traveled man, he still found his native

Bardowa a place �with no equal of agricultural crops and fish.� Aided

by Sankaradeva�s extraordinary personality and his voice of

thunder, Bardowa became the centre of Vaishnavite

movement and the cultural awakening that accompanied it.

Sadly, he would soon leave Bardowa never to return.

Homeless

After a period of relative stability, trouble started anew

at Bardowa. Matters reached serious proportions when the

Kacharis attacked the Bhuyas. Bhuyas were now too weak to resist;

Sankaradeva advised his people to move north of the river

Brahmaputra. Around 1516, they abandoned their homes, never to return.

Bardowa would remain shrouded in anonymity for the next 150 years.

All Sankaradeva had ever wanted was to share his

faith with a wider audience and this was being denied to him. He was now

ousted from what had been the ancestral home for generations of Bhuyas.

He began his search for a new shelter, for himself and for his people.

They camped at several places on the north bank of the

Brahmaputra,

including Rauta and Gangmau, forced each time to move by one

warring faction or another. The beleaguered group finally reached

Dhuwahat in the island of

Majuli, a part of the Ahom kingdom. Here, they would serve

the Ahom king loyally under the leadership of Hari Bhuya, Sankaradeva�s

son-in-law, and also enjoy a certain degree of autonomy.On the bank of

the little stream Dhuwa, Sankaradeva established what would become

Belaguri xatra. Due to erosion by the

Brahmaputra,

the Majuli Belaguri xatra has been relocated to Narayanapur on the

north bank.

Sankaradeva

and his people had a considerably long stay at Dhuwahat. But their

relationship with the Ahom rulers always remained tenuous, predicated

wholly upon their paying obeisance to Ahom supremacy. Offering harbour to

the Bhuyas did not stop the Ahom from persecuting them,

particularly when under pressure from the priesthood. This apparent

dichotomy in the attitude of the ruling fraternity towards his religion

marked Sankaradeva's lifetime. Time and again he would be summoned

to the royal court to prove the validity of his religion through verbal duels which he invariably won.

Interestingly, the Sikhs would undergo a similar ordeal

with the Mughal rules but with radically different results; the

pacific followers of their founder, Guru Nanak, would turn into the

militant khalsa under the tenth and last Guru, Gobind Singh

(1666-1708).

In 1497, Suhungmung had become the first Ahom king

to assume a Hindu name. It signaled the king�s desire to merge with the

mainstream as also greater clout for the priesthood. Despite this,

Sankaradeva�s tireless efforts began to bear fruit. His school of

thought took root; his religion caught the imagination of the people. The

number of his followers grew, and so did the opposition of the clergy.

This dialectic with the priesthood would continue till the very last days

of his life. He was soon sent help under unexpected circumstances.

In 1522, Madhava is a 32-year-old Kayastha

youth, proficient in philosophy, logic, Sanskrit poetry as well as in

accountancy, and also a staunch Sakta. When his mother became ill,

Madhava decided to sacrifice two white goats to the Mother Goddess

as votive offerings. He hurried to the side of his sick mother,

instructing his brother-in-law, Gayapani, to buy the goats.

Madhava was unaware that Gayapani had already embraced

Vaishnavism under Sankaradeva, and taken the name Ramadasa.

Gayapani, a Vaishnava now, did not buy the sacrificial goats.On

learning this and being given the reason for it, a furious Madhava

chose to confront Sankaradeva.

A bitter verbal duel ensued between the two: Sankaradeva,

exponent of Bhakti, and Madhava, quoting from scriptures in

defense of his Sakta beliefs. After four and a half hours,

Sankaradeva turned to the following lines from the Bhagawata Purana:

�As the branches, leaves, and foliage of a tree are

nourished by the pouring of water only at the root of the tree, as the

limbs of the body are nourished by putting food only in the stomach, so

all gods and goddesses are propitiated only by the worship of

Krishna.�

Hearing this, Madhava fell silent; he was now

convinced that Sankaradeva�s was the correct stand. He promptly

fell at Sankaradeva�s feet, accepting him as his Master. From that

moment on, he dedicated his life to the cause of Bhakti and to

Sankaradeva, and remained a bachelor despite being goaded by

Sankaradeva himself to marry. Thus, what began as a routine

confrontation between two scholars--- both well-versed in the scriptures,

each firm in his religious belief�developed into a defining moment in

Assamese Vaishnavism.

Sankaradeva

now had in Madhaba an able associate who was a scholar, a poet, and

a fine singer. The religion of Bhakti flourished and the number of

devotees increased manifold. At the age of 73, Sankaradeva had

found his chief apostle and, as he realized, his religious successor.

Sankaradeva named Madhaba his prana bandhava, his soul

mate.

The growing popularity of Sankaradeva�s religion

would now cause his downfall.

Homeless Once More

Sankaradeva�s

relations with the Ahom had always been under a lot of strain. Things took

a turn for the worse in 1539 when Suklenmung became king after

killing his father, Suhungmung. Matters came to a head during an

elephant-catching operation. The Ahoms accused Hari Bhuya of

non-cooperation and dereliction of duty, arresting him together with

Madhava. After a summary trial, the Ahoms executed Hari Bhuya,

and detained Madhava for several months. Facts came to light only

after Madhava reached home upon his release. The fraught relations

with the Ahoms finally snapped. Sankaradeva realized this was all a

ruse engineered by the Brahmin clergy; the time had come for him and his

people to seek new pastures.

All through his adult years, Sankaradeva and his

people had suffered such humiliations and disturbances to their peace.

These militated against their settling down anywhere for long. Since

leaving Bardowa, he had set up home in no less than seven different

places, driven out each time by divisive forces. He now longed for clement

surroundings in which to propagate his faith.

His wishes were fulfilled when Naranarayana

(1540-1584) ascended the throne of the neighbouring western kingdom of

Koch Behar. Schooled in

Varanasi, Naranarayana was a �man of mild and studious disposition, more addicted to

religious exercise and conversation with learned men than to the conduct

of State affairs. In all questions of politics, Chilarai, his

brother and Commander-in-Chief of the army, seems to have possessed and

overwhelming influence; he was the moving spirit in every adventure.�

The two princely brothers, Naranarayana and Chilarai, soon

gained reputation as lovers of learning.

Two prominent Bhuyas in the west, who had fled the

Koch kingdom during the reign of Bisva Singha, Naranarayana�s

father, now formed an alliance with the new king. They agreed to serve in

his army and help in his attack on the Ahoms. The western Bhuyas

also facilitated a safe passage for their eastern brethren to leave their

tormentors in the Ahom kingdom and migrate to the safer haven of the Koch

kingdom.

And in Chilarai, Sankaradeva would find his most

loyal patron.

Migration to

Koch Kingdom

In 1546, Sankaradeva and his followers set sail for

Koch Behar, taking the river route from Dhuwahat. While

selecting a site for a xatra, other than the practical

consideration of river communicability, the key determinant was the

�availability of grains, vegetables and fish. The travelers made

several attempts at finding a suitable location. They first set up camp at

Palengdi-bari near Barpeta town, before finally settling at Pat-bausi,

a few kilometers away.

At first, Naranarayana did not take too kindly to

Sankardeva. But he was won over after he heard Sankaradeva's devotional songs and saw his scholarly prowess in debates

with the priests. A great patron of learning, Naranarayana�s

religious ambivalence is evident in his allowing Sankardeva to

preach his liberal faith of Bhakti, while also helping rebuild the

Sakta temple at Kamakhya, destroyed by the

Mohammedans.

The brothers, Naranarayana and Chilarai, together took the

kingdom of Koch

Behar to great heights. They defeated the powerful Ahoms and erected a

fort at Narayanpur, the Kacharis were easily overcome and

the kings of Manipur, Jaintia, Tippera and Sylhet meekly

surrendered. The Koch kingdom, in its prime, extended from the river

Karatoya in the west to central Assam in the east. Naranarayana

would, however, be the last king of undivided Koch Behar.

Chilarai

became a staunch supporter of Sankaradeva and developed kinship

with him when he married into the saint�s family. During his pat-bausi

days, Sankaradeva paid regular visits to the court of

Naranarayana. While there, he would stay with Chilarai who had

built a xatra for him at Bheladenga, near the capital of

Koch Behar. This xatra would twice be washed away, before

being established at its present site, known as Madhupur xatra.

Around 1550, soon after settling down at Pat-bausi,

Sankaradeva embarked on his second pilgrimage, accompanied by 120

devotees, including Madhavadeva. They visited Puri, which

always held a special place in Sankaradeva�s heart. Unlike the

first, this pilgrimage turned out to be a short sojourn. It is said that

Sankaradeva�s wife tutored Madhavadeva to decline to

accompany him to Vrindavan, fearing her husband might decide to stay on

and not return home. The plan worked; after six months in Puri, the

pilgrims returned home. Sankaradeva too no doubt aware of the

time left to him in which to carry out his work.

His most creative period was now imminent. For the last

eighteen or twenty years of Sankaradeva�s life, Pat-bausi

was his permanent place of residence. At last, he had come to the serenity

he had sought all his life. His prodigious creative output during this

period speaks of that arrival.

Sankaradeva�s

major poetical and dramatic works were composed at Pat-bausi

between 1546-1568. The last sections of the Kirtana-ghosa were

set down, and the Bhagawata X-Adi was rendered into Assamese

verse, these two being the key texts of Assamese Vaishnavism. All

his dramas, with the exception of Vipra-patni-prasada, were

composed and produced during his stay in Koch Behar. Other works

include the Bhagawata I,II,XI and XII, and some lyrics belonging to

the genres of Bargeet and Bhatima. During this period,

Sankaradeva also wrote the Totaka hymn and complied his

treatise, Bhakti-ratnakara, culled from the Bhagawata-purana,

the Bhagawadgita, and other Vedic texts.

This brings us to Sankaradeva�s legacy, intrinsic to

any study of the man.

Literary Works

Sankaradeva�s literary

output is prodigious, remarkable for a religious writer. He adopted

several forms of literature: prose, verse and poetical prose, translations

or adaptations, compilations from different texts, songs and lyrics,

longer narratives and a doctrinal treatise. He wrote in three

languages---Assamese, Assamese Brajabuli and Sanskrit. Equally

proficient in all three, he would choose the one most suited for the

purpose and the target audience in mind.

Propagation of his

religion was Sankaradeva�s chief concern. So, he wrote most of his works

in simple Assamese to make them accessible to the common people. His

Bargeets and Ankiya Nats are in Assamese Brajabuli, in

keeping with the pan-Indian tradition. Brajabuli further affords

the use of fanciful language making for heightened drama in the Ankiya

Nats. Sankaradeva wrote Bhakti Ratnakara and the Totaka

hymn in Sanskrit to silence the skeptics who doubted his mastery over the

language.

Vaishnava

poets of the time labored within the framework of spiritual ideals. This

put a curb on their creative freedom. Sankaradeva circumvented the

limitation adroitly: he invoked the sentiment of Bhakti in his

writings and gave a new vigor to Assamese literature. His translations of

Sanskrit scriptures into Assamese are in reality transcriptions, enriched

with a visceral energy his own. His was a new diction; a style and rigour

which provided a model for generations of poets and above all, laid bare

the beauty of plain homely Assamese. Assamese literature is fortunate to

be so enriched by the writings of a man without any literature ambitions,

his only object as a writer being to bring his faith to the people. The

enduring body of work he left behind makes him, nearly 500 years after his

death, as much a man of letters as one of God. His most popular works, the

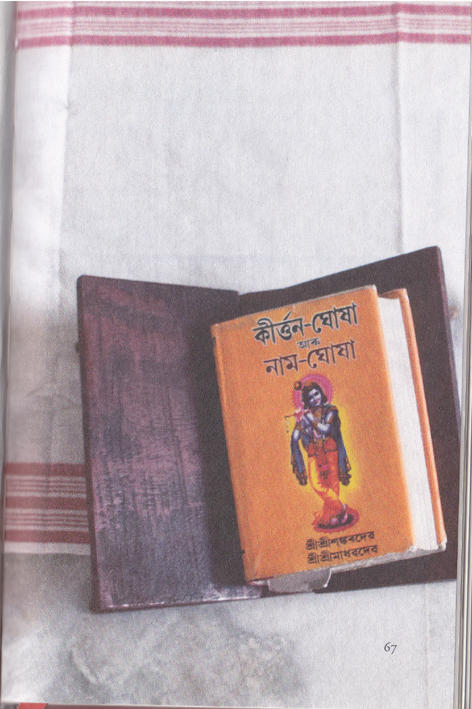

Kirtana Ghosa and the Bhagawata X-Adi, are mainstays to this

day in every Assamese home.

The Kirtana Ghosa,

or simply Kirtana, is the first of Sankardeva�s work written

specially for the purpose of propagating his faith. It describes �the

divine attributes and activities of Lord Krishna in a language within the

reach of the masses, that they may understand them and sing them in

devotion to the Lord.� While trying to expound his religion, �the

propagandist is not a dry bone preacher but a genius adroit in his appeal,

felicitous in the choice of language and expert in evoking all the poetic

and aesthetic sentiments of devotion.�

Every Kirtana is

meant for more than one voice, and consists of two parts: the Ghosa or

refrain, and a number of Padas or verses.

For example:

�Oh Hari,

I hold on to thy feet and seek refuge;

Oh Gopala,

in the midst of the ocean of worldliness,

Oh Madhava,

I have been submerged,

Recollecting this, I lose sleep.�

�Oh fellow men, save

yourselves from imminent death, Through uttering Rama and Rama.�

The verses carry his

message to his devotes with a simple immediacy:

�It is the essence of

all scriptures that with Hari Nama, one can be saved from this world. Of

the Puranas, the Bhagawata the Agamas, the Vedantas, this is the gist.�

�All the effects

available through pilgrimage to all the scared places, all the sacrifices,

the various acts of charity, observance of vows, and the achievements,

obtained by the Brahmacharis, householders, ascetics and the

Sanyasis all combined together are achieved at the very sight of Lord

Krishna, further description is useless. On the whole, men would achieve

emancipation if they, upon seeing

Krishna, bow down to Him.�

The rendering of the

Bhagawata marks a turn in the development of Assamese poetry. Sankaradeva translated the

Bhagawata not into literary Assamese but into idiomatic Assamese. It

is of an interpretative nature, written in a homely and direct style,

accessible even to the unlettered. After Kirtana, Sankaradeva�s

Bhagawata X-Adi is the most popular Vaishnava scripture by

virtue of its sustained storytelling, rich poetry and fine versification.

Extant literary works

composed by Sankaradeva amount to 26 in number. The Bhagawata IX,

often ascribed to him, has not been found, while the Nimi-Navasiddha

sangbad, part of Bhagawata XI, is sometimes catalogued

separately under kavyas. His complete works are: Kirtana-ghosa,

Gunamala; Bhagawata I,II,III (Anadi Patana), VI (Ajamil

Upakhyan), VIII (Amrita manthan & Bali Chalan), X (Adi), XI & XII; Six

Ankiya Nats, Patni Prasad, Rukmini Haran, Kaliya daman Yatra,

Keli Gopal, Parijat Haran & Sri Ram Vijay; Six Bhakti-Tatva-Kavyas:

Nimi-Navasiddha Sangbad, Bhakti Pradip, Harischandra Upakhyan, Rukmini

haran, Kurukshetra & Ramayan-Uttarakhanda; Bargeets (35 nos), Raj

Bhatima (2 nos), Deva Bhatima including Totaka hymn (3

nos), and the Sanskrit treatise Bhakti Ratnakara.

It is difficult

to fix the chronology of these works as, out of the 26, only one bears the

date of composition within the body of the text. However, Dr. Maheswar

Neog, eminent Vaishnavite scholar, makes an attempt, based on the

tenor of the saint�s compositions. It is said that Sankaradeva�s writing

from the early (Bhuya) period, pre-1516, is characterized by

youthful gaiety and exuberance; the middle (Ahom) period from 1516

to 1546- a period of great unrest and obstruction-is marked by a note of

self-criticism; while the final period in Koach Behar, from 1546 to 1568,

is marked as the most peaceful and also the most creative period in his

life.